Washington and Lee University School of Law Washington and Lee University School of Law

Washington and Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons Washington and Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons

Scholarly Articles Faculty Scholarship

2016

When “Disruption” Collides with Accountability: Holding When “Disruption” Collides with Accountability: Holding

Ridesharing Companies Liable for Acts of Their Drivers Ridesharing Companies Liable for Acts of Their Drivers

Alexi Pfeffer-Gillett

Washington and Lee University School of Law

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlufac

Part of the Agency Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Torts Commons, and the

Transportation Law Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Alexi Pfeffer-Gillett, When Disruption Collides with Accountability: Holding Ridesharing Companies Liable

for Acts of Their Drivers, 104 Calif. L. Rev. 233 (2016).

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Washington and Lee University

School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles by an authorized

administrator of Washington and Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please

contact [email protected].

233

When “Disruption” Collides with

Accountability: Holding Ridesharing

Companies Liable for Acts of Their

Drivers

Alexi Pfeffer-Gillett*

When Uber launched in San Francisco in 2010, it took the city

by storm. Here was a high-tech transportation service that seemingly

did everything better than taxicabs: it was more convenient, more

accessible, more comfortable, and even cheaper in many instances.

Uber’s initial success inspired a number of lower-cost, non-

professional “ridesharing” options, which have flourished.

Some skeptics, including taxicab operators, have decried the

arrival of these peer-to-peer ridesharing services, now classified by

regulators as Transportation Network Companies (TNCs). While

such complaints could be easily dismissed as the dying groans of a

“disrupted” industry, a string of passenger safety incidents has

raised doubts about whether these services are ready to safely

replace traditional transportation services.

One critical gray area for consumers is whether injured parties

can recover from TNCs rather than their drivers alone. This Note

argues that TNCs should be liable for acts of their drivers, and it

provides a novel approach—the nondelegable duty rule—that has yet

to be argued by plaintiffs in existing cases. Such an approach will

place responsibility where it should be: on the companies profiting

from the drivers and passengers. More importantly, preventing TNCs

from exploiting regulatory loopholes has broader implications for the

rapidly growing “sharing economy.”

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15779/Z380854

Copyright © 2016 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. (CLR) is a

California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their

publications.

* J.D. Candidate, University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, 2016. Special thanks to

Kathryn Abrams, Chris Hoofnagle, Joseph Lavitt, Ted Mermin, and Saira Mohamed for their feedback

and encouragement.

234 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

Introduction ...................................................................................................... 234!

I. The Challenge of Classifying TNCs and Their Drivers ............................... 239!

A.! TNCs as Online Platforms ............................................................ 240!

B.! TNCs as Employers ...................................................................... 242!

1.! The Presumption in Favor of an Employment Relationship .. 244!

2.! The Case Against Respondeat Superior Liability ................... 244!

a.! Visual Representations .................................................... 245!

b.! Accountability to Dispatcher ........................................... 246!

c.! Vehicle Ownership .......................................................... 247!

d.! Non-Competes and Other Contractual Provisions ........... 248!

e.! Termination ...................................................................... 249!

3.! Driver Victories over TNCs .................................................... 250!

II. The Promise of the Nondelegable Duty Doctrine ....................................... 252!

A.! TNC Drivers as Independent Contractors ..................................... 254!

B.! Public Franchise or License .......................................................... 255!

C.! Risk to Public Safety .................................................................... 259!

III. Policy Recommendations .......................................................................... 262!

A.! Background Checks ...................................................................... 262!

B.! Employment Status ....................................................................... 263!

C.! Public Representations .................................................................. 263!

D.! Minimum Time Requirements ...................................................... 264!

Conclusion ....................................................................................................... 266!

INTRODUCTION

On New Year’s Eve of 2013 in San Francisco, a driver for the popular

“ridesharing” service uberX failed to yield to a six-year-old girl and her family

at a crosswalk.

1

The driver struck and killed the little girl and left the mother

and brother injured.

2

The parents of the girl sued not only the driver but also

Uber Technologies, LLC, uberX’s parent company.

3

According to their

complaint, the uberX driver hit and killed the girl while he was logged into

Uber’s phone application and searching for customers.

4

The girl’s mother has

since stated that she could “see the light from the cell phone” cast on the

driver’s face immediately before the accident.

5

The case implicated

1. David Streitfeld, Rough Patch for Uber Service’s Challenge to Taxis, N.Y. TIMES (Jan. 26,

2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/27/technology/rough-patch-for-uber-services-challenge-to-

taxis.html [http://perma.cc/4YQT-CWRZ].

2. Id.

3. Complaint for Damages and Demand for Trial by Jury at 1, Liu v. Uber Techs., Inc., No.

CGC-14-536979 (Cal. Super. Ct. Jan. 27, 2014) [hereinafter Liu Complaint].

4. Id. at 5.

5. Brad Stone, Invasion of the Taxi Snatchers: Uber Leads an Industry’s Disruption,

BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK (Feb. 20, 2014), http://www.businessweek.com/printer/articles/184857-

invasion-of-the-taxi-snatchers-uber-leads-an-industrys-disruption [http://perma.cc/QWB9-KVK8].

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 235

California’s distracted-driving law

6

and, more importantly for the plaintiffs,

whether Uber could be held liable for the negligence of one of its drivers.

7

Uber immediately attempted to distance itself from any responsibility for

the girl’s death. In a statement released the following day, Uber first extended

condolences to the family of the girl, but then noted: “The driver in question

was not providing services on the Uber system during the time of the

accident.”

8

In other words, the company did not consider a driver logged into

Uber’s phone application and searching for fares to be “providing services” on

its behalf. Of course, to the grieving family, this technicality was irrelevant.

The driver may not have been actually transporting or on his way to transport

anyone, but he was benefitting Uber by making himself available for passenger

ride requests.

The New Year’s Eve death may be the highest profile incident for

ridesharing services, but it is far from the only one for these companies, which

are now classified by California regulators as Transportation Network

Companies (TNCs). Uber customers have alleged numerous incidents of driver

misconduct, including driver negligence,

9

sexual harassment,

10

and even

kidnapping.

11

And a Chicago Tribune investigation revealed that Uber failed to

properly screen criminal records of “thousands of drivers,” letting them operate

on Uber’s service “despite not knowing whether or not they had felony

convictions.”

12

Meanwhile, Lyft, another TNC, experienced its first passenger

6. CAL. VEH. CODE § 23123 (West 2014).

7. See, e.g., Carmel DeAmicis, Exclusive: Uber Driver Accused of Assault Had Done Prison

Time for a Felony, Passed Background Check Anyways, PANDO (Jan. 6, 2014),

http://pando.com/2014/01/06/exclusive-uber-driver-accused-of-assault-passed-zero-tolerance-

background-check-despite-criminal-history [http://perma.cc/4LWS-SQMW]; Stone, supra note 5;

Kale Williams & Kurtis Alexander, Uber Sued over Girl’s Death in S.F., S.F. CHRONICLE (Jan. 28,

2014), http://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Uber-sued-over-girl-s-death-in-S-F-5178921.php

[http://perma. cc/BNJ8-4N9B].

8. Andrew, Statement on New Year’s Eve Accident, UBER BLOG (Jan. 1, 2014),

https://blog.uber.com/2014/01/01/statement-on-new-years-eve-accident [https://perma.cc/VK3K-

BA5E]. In response to general criticisms about the Uber application’s potential to distract drivers,

Uber’s CEO stated: “[T]he technology Uber provides its partners is far safer than anything the taxi

industry offers.” Stone, supra note 5.

9. See, e.g., Complaint at 2–3, Bishop v. Uber Techs., Inc., No. 37-2014-00037935-CU-PA-

CTL (Cal. Super. Ct. Nov. 5, 2014) [hereinafter Bishop Complaint].

10. Olivia Nuzzi, Uber’s Biggest Problem Isn’t Surge Pricing. What If It’s Sexual Harassment

by Drivers?, DAILY BEAST (Mar. 28, 2014), http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/03/28/uber-s-

biggest-problem-isn-t-surge-pricing-what-if-it-s-sexual-harassment-by-drivers.html [http://perma.cc

/8JLM-VDC5].

11. Julie Zauzmer & Lori Aratani, Man Visiting D.C. Says Uber Driver Took Him on Wild

Ride, WASH. POST (July 9, 2014), http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/dr-gridlock/wp/2014/07/09

/man-visiting-d-c-says-uber-driver-took-him-on-wild-ride [http://perma.cc/S3C9-BU9Z].

12. Leonor Vivanco & Cynthia Dizikes, Gaps in Some Ride-Sharing Firms’ Background

Checks, CHI. TRIB. (Feb. 14, 2014), http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2014-02-14/news/ct-rideshare-

background-checks-met-20140214_1_background-checks-ride-sharing-drivers [http://perma.cc/H3TA

-8MU5]. Uber released a statement, on the same day, that it had had improved its background checks

and deactivated the driver revealed by the Tribune to have a prior felony. Nairi, Statement on Chicago

236 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

fatality on November 1, 2014.

13

Despite these recent incidents, there is still

scant, if any, case law addressing whether TNCs can be liable for tortious acts

of their drivers.

14

Given such a void, this Note addresses TNC liability in a way

that reflects the unique nature of the services these companies provide and their

distinctive employment arrangement with drivers.

The issue is an important one because TNCs, and the sharing economy

generally, are growing at a rapid—and largely unchecked—pace. When Uber

launched in San Francisco in 2010, it took the city by storm. It was a high-tech

service that seemingly did everything better than taxicabs: it was more

convenient, more accessible, more comfortable, and even cheaper in many

instances. Uber’s initial success inspired lower-cost, nonprofessional

“ridesharing” options—including uberX, Lyft, and Sidecar—which have

flourished. These services are able to operate cheaply, at least in part, because

the drivers (unlike taxicab drivers) carry noncommercial licenses and use their

personal vehicles rather than company cars.

15

In addition, passengers and

drivers find each other using a phone application, cutting out the need to

employ full-time dispatchers.

16

But harsh realities are beginning to catch up to TNCs. Taxicab operators

have rebelled against TNCs since their inception, arguing that they unfairly

benefit from loopholes and a lax, if not completely nonexistent, regulatory

framework. Many commentators initially dismissed these complaints as the

dying groans of an outmoded industry that had been successfully “disrupted,”

17

business speak for when a new market entrant overtakes an existing industry by

UberX Background Check, UBER (Feb. 14, 2014), https://blog.uber.com/chiuberxbackgroundcheck

[http://perma.cc/JS7Z-ZL99]. In addition to the risk of noncompliance, California and other states

require TNCs to conduct significantly less rigorous background checks than those required of taxicab

companies. See DeAmicis, supra note 7. The appropriateness of conducting pre-hiring background

checks for felonies is certainly debatable, but it is outside the scope of this Note.

13. Ellen Huet, Lyft’s First Fatality: Passenger Dies in Crash Near Sacramento, FORBES

(Nov. 2, 2014), http://www.forbes.com/sites/ellenhuet/2014/11/02/lyfts-first-fatality-passenger-death-

crash-sacramento [http://perma.cc/3HVA-GQBG].

14. The case over the Uber driver’s New Year’s Eve accident, for example, ultimately settled,

leaving the question of Uber’s legal liability unanswered. See Dan Levine, Uber Settles Wrongful

Death Lawsuit in San Francisco, REUTERS (July 15, 2015), http://www.reuters.com/article/2015

/07/15/us-uber-tech-crash-settlement-idUSKCN0PO2OW20150715 [http://perma.cc/U829-P46G].

15. See infra Part II.B.i.

16. See infra Part II.B.i.

17. See, e.g., Nick Bilton, Disruptions: Ride-Sharing Upstarts Challenge Taxi Industry, N.Y.

TIMES (July 21, 2013, 11:00 AM), http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/21/disruptions-upstarts-

challenge-the-taxi-industry [http://perma.cc/Y5RC-F8WH]. Indeed, ridesharing has undercut the

taxicab industry: in San Francisco, for example, the average number of rides per month dropped by

nearly 65 percent from March 2012—when ridesharing services were just starting—to September

2014. Jessica Kwong, Report Says SF Taxis Suffering Greatly, S.F. EXAMINER (Sept. 16, 2014),

http://archives.sfexaminer.com/sanfrancisco/report-says-sf-taxis-suffering-greatly/Content?oid

=2899618 [http://perma.cc/CFM9 -5DS5].

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 237

harnessing technology in novel ways or creating a new business model.

18

The

complaints and passenger safety incidents, though, have undermined the idea

that ridesharing services are ready to replace traditional taxi services.

Amid this uncertainty, courts will need to answer some critical questions:

If a TNC customer gets severely injured in an accident because the driver is

operating recklessly, will the company step in to cover the customer’s medical

costs beyond the driver’s insurance?

19

If a third-party bystander is killed while

a TNC driver is distractedly looking for fares on his cell phone, would the

company be liable to the bystander’s estate?

20

Both of these situations have

happened and have resulted in lawsuits.

21

In addressing the gray area of TNC tort liability, this Note focuses on

California law. It does so because California is the birthplace of many

ridesharing companies and remains one of their largest markets.

22

As the home

of Silicon Valley, California policy makers have also led the way in creating

new regulations to cover ridesharing services.

Perhaps most significantly, California has begun requiring that all TNC

vehicles carry significant accident insurance—a step that helps protect

passengers and bystanders.

23

Yet two problems remain: First, the insurance

coverage is inadequate. For example, even after California’s new insurance

requirements took effect on July 1, 2015, drivers who are available for rides on

the TNC application but not actually transporting anyone still carry only

$50,000 worth of insurance per person for death and personal injury.

24

In a case

where a bystander is killed, the potential award could far exceed the $50,000 of

insurance coverage. Second, just because TNCs now carry insurance does not

mean the TNC companies and their insurers will happily pay out every claim

18. See A.W., What Disruptive Innovation Means, ECONOMIST (Jan. 25, 2015, 11:50 PM),

http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2015/01/economist-explains-15

[http://perma.cc/7BJE-SA66].

19. California has recently increased the minimum insurance levels that companies like Uber

are required to carry while transporting drivers. CAL. PUB. UTIL. CODE § 5433 (West 2014). But

simply possessing insurance does not necessarily keep companies like Uber and their insurance agents

from attempting to avoid paying damages. See, e.g., Answer of Defendants, Bishop v. Uber Techs.,

No. 37-2014-00037935-CU-PA-CTL (Cal. Super. Ct. Dec. 29, 2014) [hereinafter Uber Bishop

Answer] (disclaiming all responsibility for passenger injury at the hands of an allegedly negligent

driver).

20. Uber’s insurance would also cover this type of incident, but only for a fraction of the

amount available when a driver is transporting a passenger. CAL. PUB. UTIL. CODE § 5433.

21. Bishop Complaint, supra note 9, at 2–3 (passenger injury); Liu Complaint, supra note 3, at

4 (bystander death).

22. Both Uber and Lyft were founded in San Francisco. See Adam Lashinsky, Uber: An Oral

History, FORTUNE (June 3, 2015), http://fortune.com/2015/06/03/uber-an-oral-history

[http://perma.cc/5H8T-YZVN]; Nicholas Carlson, Lyft, A Year-Old Startup That Helps Strangers

Share Car Rides, Just Raised $60 Million From Andreessen Horowitz and Others, BUS. INSIDER (May

23, 2013), http://www.businessinsider.com/lyft-a-startup-that-helps-strangers-share-car-rides-just-

raised-60-million-from-andreessen-horowitz-2013-5 [http://perma.cc/P3HG-4VK7].

23. CAL. PUB. UTIL. CODE § 5433.

24. Id.

238 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

made by a passenger or bystander. Indeed, Uber disclaimed all liability after a

passenger in San Diego sued the company and its driver for negligent driving.

25

And Uber made this claim even though the car presumably carried the required

$1 million insurance policy.

26

California’s insurance requirements might help,

but they do not solve the passenger and bystander safety issues.

This Note seeks to find a path for plaintiffs to hold TNCs liable for acts of

their drivers. And it does so in a way not yet argued by plaintiff-side attorneys.

So far, injured parties have alleged that drivers and TNCs have an employment

relationship that creates vicarious liability.

27

Although this theory could be

persuasive—indeed, courts have found an employer-employee relationship

between drivers and TNCs in the employee benefits context

28

—it would be

unwise for plaintiffs to condition all their claims on establishing that TNC

drivers are employees, a complex and subjective test. As one federal judge said

of a case concerning the employment relationship presented by TNCs, “The

test the California courts have developed over the 20th Century for classifying

workers isn’t very helpful in addressing this 21st Century problem.”

29

Instead,

the jury in that case had been “handed a square peg and asked to choose

between two round holes.”

30

This Note argues in the alternative that TNCs’

responsibility for acts of their drivers need not be dependent on “20th century”

employment tests; instead, the companies can and should be held liable because

they have a “nondelegable duty” to protect the safety of passengers and the

general public.

Part I explores the common arguments advanced by both TNCs and the

plaintiffs hoping to recover from them. It then notes, with cautious optimism, a

number of employment benefits cases in which individual drivers have

successfully argued that they are employees of TNCs. Part II suggests a new

perspective through which to define the relationship between TNCs and

drivers, one that could effectively hold TNCs liable while acknowledging the

25. See Bishop Complaint, supra note 9.

26. See Insurance Requirements for TNCs, CAL. PUB. UTIL. COMM’N, http://www.cpuc.ca.

gov/PUC/Enforcement/TNC/TNC+Insurance+Requirements.htm [http://perma.cc/26V2-Z4SW] (last

modified July 6, 2015).

27. Bishop Complaint, supra note 9, at 3–4; Liu Complaint, supra note 3, at 3–4.

28. State agencies in both California and Florida have found that the specific drivers bringing

suit over employment benefits were indeed employees and therefore entitled to benefits. See Alyson

Shontell, California Labor Commission Rules an Uber Driver Is an Employee, Which Could Clobber

the $50 Billion Company, BUS. INSIDER (June 17, 2015), http://www.businessinsider.com/california-

labor-commission-rules-uber-drivers-are-employees-2015-6 [http://perma.cc/H3GB-RHPJ]

(California); Robert W. Wood, Florida Says Uber Drivers Are Employees, But FedEx, Other Cases

Promise Long Battle, FORBES (May 26, 2015), http://www.forbes.com/sites/robertwood/2015/05/26

/florida-says-uber-drivers-are-employees-but-fedex-other-cases-promise-long-battle [http://perma.cc

/C4NT-ZSTL] (Florida).

29. Ellen Huet, Juries to Decide Landmark Cases Against Uber and Lyft, FORBES (Mar. 11,

2015), http://www.forbes.com/sites/ellenhuet/2015/03/11/lyft-uber-employee-jury-trial-ruling

[http://perma.cc/9SZJ-PZZ3] (quoting U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria).

30. Id. (quoting U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria).

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 239

uniquely modern relationship the companies have with their drivers. The

nondelegable duty doctrine is an equitable rule that bars certain types of

employers—those that are engaged in a dangerous activity and operate under a

public license or franchise—from avoiding liability for acts of their

independent contractors.

31

After laying out strategies for plaintiffs, Part III

offers policy recommendations that seek to make TNCs safer and resolve

lingering ambiguities about TNC operations.

As with many disruptive industries before them, TNCs appear to be

coming to the end of their free-for-all period of uninhibited growth. It is time

for courts and policy makers to begin closing the loopholes from which TNCs

have benefitted and take a tangible step toward maintaining consumer

protections in this era of startups and deregulation. Only then will the public be

able to judge whether TNCs are the wave of the future or mere opportunists

capitalizing on regulatory carelessness.

I.

THE CHALLENGE OF CLASSIFYING TNCS AND THEIR DRIVERS

TNCs are a novel phenomenon that will require courts to adapt existing

legal doctrines to determine liability for driver actions. With vast sums of

money at stake, it is no surprise that TNCs and regulators have already butted

heads over the extent to which the services bear responsibility for public safety.

For their part, TNCs have tried to argue that they are merely technology

“platforms” that connect drivers offering services to prospective passengers,

and therefore they should not be liable for acts of their drivers. By contrast, the

California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) and the state’s legislature have

begun creating new TNC regulations with the express concern of protecting the

general public from the potential dangers of using the services.

32

It remains unclear, though, whether victims have any legal recourse

against TNCs for the acts of their drivers. TNCs have sought to minimize their

relationship with drivers

33

—something that would help them avoid liability. At

the other end of the spectrum, plaintiffs have argued that TNCs have strong,

employer-level relationships with their drivers,

34

which could lead to recovery

31. See infra Part II.

32. See infra Part II.C.

33. See, e.g., Lyft Terms of Service, LYFT (Sept. 11, 2015), https://www.lyft.com/terms

[https://perma.cc/2ANF-RZQA] (“The Lyft Platform provides a marketplace where persons who seek

transportation to certain destinations (‘Riders’) can be matched with persons driving to or through

those destinations (‘Drivers’).”); Terms and Conditions, UBER (Apr. 8, 2015),

https://www.uber.com/en-US/legal/usa/terms [https://perma.cc/HNP6-KG22] (“UBER DOES NOT

GUARANTEE THE QUALITY, SUITABILITY, SAFETY OR ABILITY OF THIRD PARTY

PROVIDERS.”); Terms of Services, SIDECAR (Dec. 12, 2014), http://www.side.cr/policies/terms-of-

services [http://perma.cc/RN9X-DN7C] (“Sidecar drivers explicitly agree that he or she is not an

employee or independent contractor of Sidecar, but a user of the Sidecar mobile app and a TNC driver

as defined by the California PUC or other regulatory agency with jurisdiction over our service.”).

34. See, e.g., Liu Complaint, supra note 3, at 3–4.

240 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

under traditional strict liability theories like respondeat superior. Both of these

portrayals are flawed. TNCs exercise far more control over vendors (drivers)

than passive buying and selling platforms like eBay and Craigslist. But the

amount of control may not fit within the traditional common law definition of

an “employer” because drivers retain significant discretion as to how, when,

and where they operate.

A. TNCs as Online Platforms

Since their inception, TNCs have clung to the argument that they are mere

platforms connecting passengers with drivers, and therefore cannot have any

liability for driver actions. Uber has been particularly audacious, arguing that it

should be exempt from the CPUC’s and any other state or local transportation

agency’s jurisdiction because it is not a transportation company at all.

35

The

company likened uberX to Google’s PowerMeter service, which is not subject

to normal energy utility regulations because it merely monitors energy usage

and does not require consumers to pay a fee for the service.

36

The CPUC

quickly shot down this analogy, noting that uberX does far more than merely

“show customers maps of available cars, without giving them a way to book a

ride and without controlling or taking a share of the fare.”

37

Judges have also weighed in, and their initial reactions are even less

favorable to TNCs. “The idea that Uber is simply a software platform, I don’t

find that a very persuasive argument,” said one federal judge in response to a

lawsuit concerning whether Uber had a duty to pay drivers minimum wage.

38

Indeed, TNCs do not operate in the same way as online platforms like eBay

and Craigslist, which passively connect buyers to sellers of goods. TNCs may

likewise connect passengers with drivers, but they do so in a far more extensive

manner than online selling websites. Whereas companies like eBay charge a

nominal flat rate for most listings,

39

TNCs take a significant percentage cut

35. Decision Adopting Rules and Regulations to Protect Public Safety While Allowing New

Entrants to the Transportation Industry, at 16–17, R. 12-12-011, Dec. 13-09-045, 2013 WL 10230598

(Cal. Pub. Util. Comm’n Sept. 19, 2013), http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Published/G000

/M077/K192/77192335.PDF [http://perma.cc/Z2JG-U4XZ] [hereinafter 2013 CPUC Order]; see also

Uber Bishop Answer, supra note 19, at 6 (“Uber warrants it is a technology company, not a

transportation company or common carrier . . . .”).

36. 2013 CPUC Order, supra note 35, at 15–16. Uber attorneys have also claimed that Uber is

an “intellectual property company” and drivers are not servants of Uber but rather customers of the

service. Karen Gullo, Uber and Lyft Drivers May Have Employee Status, Judge Says, BLOOMBERG

(Jan. 30, 2015), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-01-30/uber-drivers-may-have-

employee-status-judge-says [http://perma.cc/6T64-SDC9].

37. 2013 CPUC Order, supra note 35, at 16.

38. Gullo, supra note 36 (quoting U.S. District Court Judge Edward Chen). Another judge

(U.S. District Court Judge Vincent Chhabria) went even further, rejecting historical job definitions and

stating that drivers should be classified as employees. Id.

39. Traditional selling platforms like eBay generally take a flat fee for posted items. Standard

Selling Fees, EBAY, http://pages.ebay.com/help/sell/fees.html [http://perma.cc/Z7NY-AY28] (last

visited Oct. 12, 2015).

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 241

from each fare.

40

And TNCs, not the drivers, control the means of operation:

once hired, drivers generally use a TNC-issued phone for picking up

customers,

41

TNCs set the actual rates that passengers pay for each trip,

42

and

TNCs negotiate with customers over cancellation fees.

43

In other words, TNCs

have significantly more interest in and control over vendors than do typical

online selling platforms.

TNCs also play a much greater role from the perspective of the buyer of

services. Listings on eBay and Craigslist traditionally last days or even weeks,

meaning consumers have plenty of time to weigh all of their options. Buyers

can be discerning based on quality, availability, cost, uniqueness, and a host of

other subjective and objective factors. By contrast, TNC customers request

rides at the moment of need, and the TNC platform then quickly pairs the

customers with nearby drivers.

44

Such a system does not encourage—or usually

even allow

45

—consumers to extensively compare the services of each seller on

the platform. Instead, the determinative factor for a consumer is most likely

which nearby driver happens to accept the ride request first. Even if it were

possible to distinguish between drivers, doing so would be largely pointless:

TNCs require drivers to have similar cars

46

and maintain high minimum

customer ratings in order to use the platforms.

47

40. UberX, for example, recently upped its cut to 25 percent of each fare in San Francisco,

while Lyft takes 20 percent from drivers in the city. Ellen Huet, Uber Now Taking its Biggest UberX

Commission Ever – 25 Percent, FORBES (Sept 22, 2014), http://www.forbes.com/sites/ellenhuet/2014

/09/22/uber-now-taking-its-biggest-uberx-commission-ever-25-percent [http://perma.cc/47FY-

XBDX].

41. Uber is beginning to allow drivers to use personal phones, but its standard practice has

been to require drivers to use a company phone, for which drivers must pay the service $10 per week.

Luz Lazo, Uber Gives its Drivers Choice to Avoid $10 Weekly Fee for App Use, WASH. POST (Sept. 9,

2014), http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/dr-gridlock/wp/2014/09/09/uber-gives-its-drivers-

choice-to-avoid-10-weekly-fee-for-app-use [http://perma.cc/9G67-LNC4].

42. In San Francisco, for example, Uber sets the following standard rates for its uberX drivers:

$2.20 base fare; $5 minimum fare; $1 “safe rides fee”; $0.26 per minute; $1.30 per mile; $5

cancellation fee. San Francisco Bay Area, UBER, https://www.uber.com/en-US/cities/san-francisco

[https://perma.cc/2PAA-YQ28] (last visited Oct. 12, 2015).

43. Berwick v. Uber Techs., Inc., No. 11-46739 E, 2015 WL 4153765, at *6 (Cal. Dept. Labor

June 3, 2015). In June 2015, Uber instituted another requirement on both drivers and passengers when

the company prohibited guns in Uber vehicles. Dante D’Orazio, Uber Bans Drivers and Passengers

from Carrying Firearms, VERGE (June 20, 2015), http://www.theverge.com/2015/6/20/8818247/uber-

bans-guns-from-vehicles [http://perma.cc/P7H2-BV6E].

44. See, e.g., How Do I Request a Ride?, UBER, https://help.uber.com/h/7ef159ca-3674-4242-

bc0c-b29024958b26 [https://perma.cc/WFH6-5J67] (last visited Oct. 13, 2015).

45. Can I Request a Particular Driver?, UBER, https://help.uber.com/h/65f52320-43a1-4979-

b374-e9b7c7c36dae [https://perma.cc/269T-QLX3] (last visited Oct. 13, 2015).

46. Richard N. Velotta, Uber Brands Taxi Companies’ Memoranda Inaccurate, L.V. REV.-J.

(June 11, 2014), http://www.reviewjournal.com/business/economy/uber-brands-taxi-companies-

memoranda-inaccurate [http://perma.cc/25K3-AMHR] (“Uber drivers are required to drive a 2008 or

newer vehicle and undergo a vehicle inspection.”).

47. Uber, for example, frequently requires drivers to maintain a minimum rating of 4.5 out of

5 stars or higher in order to access the uberX application. Jeff Bercovici, Uber’s Ratings Terrorize

Drivers and Trick Riders. Why Not Fix Them?, FORBES (Aug. 14, 2014), http://www.forbes.com

242 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

Perhaps most importantly, eBay and Craigslist do not claim to extensively

vet sellers on their websites, nor are they required to do so by any laws. By

contrast, TNCs advertise their vetting procedures as effective ways of

protecting passenger safety,

48

and the CPUC now requires them to conduct

background checks on drivers.

49

Such a system puts the onus on TNCs, not the

individual drivers, to be accountable for safe operations.

Referral platforms and companies are not an invention of the Internet age,

and TNCs share some similarities with traditional referral services, such as

those established for childcare. Like TNCs, childcare referral companies have

some responsibility for vetting the background of the individuals providing

services. But in California, for example, individuals wishing to offer childcare

services must themselves undergo a state-run background check.

50

This means

that referral services could only hire individuals who have independently

passed background check requirements. This system is different from the

regulatory framework in which TNCs now exist because the CPUC has placed

the burden of conducting background checks on TNCs (the referrers), not on

prospective drivers (the individual service providers).

51

This difference

indicates an intent to make TNCs, rather than the drivers they refer, responsible

for ensuring that the services will operate safely.

TNCs simply have a much greater hand in the provision of vendor

services than online platforms like Google, eBay, and Craigslist, or traditional

referral services. It is therefore very unlikely that any court would find, for

liability purposes, that TNCs operate as mere platforms.

B. TNCs as Employers

Although TNCs present themselves as mere buying and selling platforms,

plaintiffs are bringing suits against the companies under the theory that these

companies operate as traditional employers of their drivers.

52

By defining the

/sites/jeffbercovici/2014/08/14/what-are-we-actually-rating-when-we-rate-other-people

[http://perma.cc/2D5W-L6MP].

48. See, e.g., Rider Safety, UBER, https://www.uber.com/safety [https://perma.cc/AJB6-5JN9]

(last visited Oct. 13, 2015). As of February 2015, Uber was advertising “background checks you can

trust.” See Safest Rides on the Road: Going the Distance to Put People First, UBER,

https://web.archive.org/web/20150217153537/https://www.uber.com/safety (last visited Dec. 21,

2015).

49. 2013 CPUC Order, supra note 35, at 3.

50. Doe v. Saenz, 45 Cal. Rptr. 3d 126, 130–31 (Ct. App. 2006) (“Before any person may

register as a trustline provider or operate, work, or be present in a licensed community care facility,

that person must obtain either a criminal record clearance or, if convicted, must apply for and obtain a

criminal record exemption from the [California] Department [of Social Services].”).

51. 2013 CPUC Order, supra note 35, at 3.

52. See, e.g., Bishop Complaint, supra note 9, at 3–4 (stating that a ridesharing driver “was

serving as the agent of” Uber and its subsidiaries, and therefore the company is vicariously liable for

the driver’s negligent driving); Liu Complaint, supra note 3, at 3–4 (stating that Uber and its

subsidiaries “were the employer of the Defendant [negligent driver], and/or his partner and/or an

agency relationship existed between them”). Although, in some contexts, there may be nuanced

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 243

TNC-driver relationship in this way, plaintiffs can argue that the TNCs are

liable through respondeat superior. Under this doctrine, “the innocent principal

or employer is liable for the torts of the agent or employee, committed while

acting within the scope of employment.”

53

Critically, respondeat superior only

applies if plaintiffs prove the employer-employee relationship. Although the

respondeat superior argument has succeeded when plaintiffs have brought

cases against taxicab companies for acts of their drivers,

54

it may be less

persuasive in regard to TNCs.

This issue was a point of contention in the New Year’s Eve lawsuit

involving the six-year-old girl struck by an uberX driver. In that case, the

plaintiffs argued that the driver was an employee of Uber, and therefore Uber

was liable under respondeat superior or a similar principal-agent theory.

55

Uber

countered that it was not liable because “[the driver] was not—and has never

been—an employee of [Uber or its subsidiary, Raiser LLC].”

56

In support of

Uber’s contention that it does not provide transportation services or employ

drivers, the company noted that it does not own the vehicles and that drivers

use their own discretion in accepting passenger ride requests.

57

According to

the company, at the time of the accident the driver had “no reason . . . to

interact with the Uber App.”

58

TNCs indeed offer a different set of facts because TNC drivers are

generally subject to less control than taxicab drivers. The remainder of this

Section explains how courts traditionally gauge employer-level control in the

differences between employer-employee and other employment relationships including principal-

agent and master-servant, this Note will not go into the weeds of those individual distinctions. Indeed,

commentators have pointed out that, in the context of tort law, the distinctions are relatively

meaningless. See, e.g., 1 MODERN TORT LAW: LIABILITY AND LITIGATION § 7:2 (2d ed. 2015) (“The

terms ‘principal’ and ‘agent,’ ‘master’ and ‘servant,’ ‘employer’ and ‘employee’ may have separate

connotations for purposes of contract authority, but the distinctions are immaterial for tort purposes. A

relationship must be established: the wrongdoer must be an employee, agent, or servant in order for a

plaintiff to invoke the doctrine of respondeat superior.”).

53. B.E. WITKIN, 3 WITKIN, SUMMARY AGENCY & EMP’T § 165, at 208 (10th ed., 2005).

54. See, e.g., Yellow Cab Coop., Inc. v. Workers’ Comp. Appeals Bd., 277 Cal. Rptr. 434,

440–41 (Ct. App. 1991) (holding that, for workers’ compensation purposes, a taxicab company

exercised employer-level control over drivers because the company controlled where drivers went,

how they behaved, driver use of radios, and—most significant—the company prohibited drivers from

operating on behalf of other companies); People v. Rouse, 249 Cal. Rptr. 281 (App. Dep’t Super. Ct.

1988) (“[T]here is substantial evidence that the driver of the taxi was an employee of L.A. Taxi.”); see

also William D. Bremer, Liability of Taxicab Company For Cabdriver’s Negligence, 41 AM. JUR. 2D

PROOF OF FACTS 239 § 5 (2014) (“The Restatement points out that one might be considered a servant

even if there is an understanding that the employer shall not exercise control over the work. As an

illustration, the Restatement notes that a full-time cook is regarded as a servant even though it is

understood that the employer exercises no control over the cooking. A typical employer of taxicab

drivers would have a similarly limited degree of control over the actions of individual drivers.”).

55. Liu Complaint at 3–4, supra note 3.

56. Answer and Affirmative Defenses of Defendants Uber Technologies, Inc., at 2, Liu v.

Uber Techs., CGC-14-536979 (Cal. Super. Ct. May. 1, 2014) [hereinafter Uber NYE Answer].

57. Id. at 3.

58. Id.

244 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

context of transportation services, and it concludes that plaintiffs should

consider alternative tactics beyond trying to create liability through an

employer-employee relationship.

1. The Presumption in Favor of an Employment Relationship

In California, plaintiffs seeking to recover from TNCs can take advantage

of a presumption that a worker is an employee rather than an independent

contractor if he is “performing services for which a license is required” or

“performing such services for [an entity] who is required to obtain such a

license.”

59

TNC drivers certainly perform work for which the TNC is required

to obtain a specialized license—stipulating precautions including driver

background checks and minimum insurance levels—as ordered by the CPUC in

its 2014 opinion.

60

As a result, drivers will be presumed to be employees and

the burden will be on TNCs to show facts that prove otherwise.

2. The Case Against Respondeat Superior Liability

Even with the presumption in favor of plaintiffs, establishing that drivers

are employees of TNCs will depend on showing that TNCs exercise a

significant amount of control over their drivers,

61

a complicated determination

that could weigh in the TNCs’ favor. The CPUC has grappled with the control

analysis for years, and the Commission has largely sided with TNCs in finding

that the companies do not have an employer-employee relationship with

drivers.

Initially, the CPUC seemed to assume that TNC drivers were employees.

In a 2012 published notice citing a number of TNCs for permitting violations,

the CPUC referred to the ridesharing companies as “charter-party carriers,” and

their drivers as “employee-drivers.”

62

The notice specifically noted the carriers’

failure to subject drivers to “pre-employment” tests before hiring them.

63

However, the CPUC largely sided with the TNCs on employment issues

in a 2014 rehearing of its 2013 rules and regulations. In this rehearing, the

Taxicab Paratransit Association of California argued that, because TNC drivers

59. CAL. LAB. CODE § 2750.5 (West 2014).

60. Order Instituting Rulemaking on Regulations Relating to Passenger Carriers, Ridesharing,

& New Online-Enabled Transp. Servs., at 12, R. 12-12-011, Dec. 14-04-022, 2014 WL 1478349 (Cal.

Pub. Util. Comm’n Apr. 10, 2014) [hereinafter 2014 CPUC Order].

61. See 3 WITKIN AGENCY & EMP’T, supra note 53, at 63; see also Bremer, supra note 54, § 5

(“In determining for the purposes of respondeat superior whether a person is an agent, the most

important test traditionally has been the right of control, that is, the right of the alleged principal to

order and control the claimed agent: the right to direct the work to be done, not only as to the result to

be accomplished, but also as to the details and method of performing the work.”).

62. Press Release, Cal. Pub. Util. Comm’n, CPUC Cites Passenger Carriers Lyft, Sidecar, and

Uber $20,000 Each for Public Safety Violations (Nov. 14, 2012), http://www.cpuc.ca.gov/NR

/rdonlyres/00BF2F95-21B8-4C72-A268-D8057BD16DFD/0/CPUCCitesPassengerCarriersLyft

SideCarandUber20000EachforPublicSafetyViolations.pdf [http://perma.cc/89HJ-U2AR].

63. Id. (emphasis added).

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 245

are not employees of the TNC, they should be required to obtain individual

charter-party carrier permits.

64

The Commission agreed that TNC drivers are

not employees, but it countered that drivers are “clearly still agents connected

with the firm” who are, therefore, exempt from individual permitting

requirements.

65

In this delicate balancing act, the Commission managed to

confer upon TNCs all the permitting benefits of an employer-employee

relationship without saddling the companies with any of the other duties that

normally come from such a relationship.

Courts, like the CPUC, may be reluctant to expand the definition of

employers to cover technology services like the kind provided by TNCs. In

dealing with traditional transportation companies, courts have relied on a

number of factors for determining employer-level control. Not surprisingly, no

single factor is generally dispositive; nor is there a clearly defined threshold for

when a worker becomes an employee.

66

And even if the test did provide bright

lines, the analysis would still depend on the factors mapping neatly onto the

TNC-driver relationship—which they don’t. The remainder of this Subsection

grapples with some of the factors courts may use when determining TNC

control over drivers.

a. Visual Representations

When taxicab and limousine drivers’ cars carry visual identifiers of the

dispatch company—such as the company’s name and telephone number—

courts and commentators have taken this as evidence that the driver is an

employee of the dispatcher.

67

Since its founding, Lyft has required on-duty

drivers to display a pink moustache on the grill or dashboard of their cars.

68

64. 2014 CPUC Order, supra note 60, at 12.

65. Id.

66. Courts and commentators have, however, weighed some factors more heavily than others.

Compare Yellow Cab Coop., Inc. v. Workers’ Comp. Appeals Bd., 277 Cal. Rptr. 434, 441 (Ct. App.

1991) (stating that a company’s prohibition on allowing its drivers to contract with other businesses

was the “most significant” factor in finding an employment relationship), with Bremer, supra note 54,

§ 7 (“Of particular importance is whether the driver was required to respond to calls . . . .”).

67. See, e.g., People v. Rouse, 249 Cal. Rptr. 281, 284 (App. Dep’t Super. Ct. 1988) (finding

an employment relationship where a taxi “displayed the name and telephone number” of the taxicab

company). Even when other factors of employer-level control are not present, it can be possible to

hold a company liable when the plaintiff reasonably assumes that the agent is an employee. See

Associated Creditors’ Agency v. Davis Eyeglasses, 530 P.2d 1084, 1100 (Cal. 1975) (“The person

dealing with the agent must do so with belief in the agent’s authority and this belief must be a

reasonable one; such belief must be generated by some act or neglect of the principal sought to be

charged; and the third person in relying on the agent’s apparent authority must not be guilty of

negligence.”).

68. Kyle VanHemert, Lyft Is Finally Ditching the Furry Pink Mustache, WIRED (Jan. 20,

2015), http://www.wired.com/2015/01/lyft-finally-ditching-furry-pink-mustache [http://perma.cc

/DV7V-SFAJ].

246 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

Uber had no comparable requirement during the company’s formative years,

69

so there was generally no way to distinguish between on-duty Uber drivers and

everyone else on the road. But in 2013 the CPUC ordered all TNC vehicles to

“display consistent trade dress (i.e., distinctive signage or display on the

vehicle)” when in service.

70

The trade dress “shall be sufficient to allow a

passenger, government official, or member of the public to associate a vehicle

with a particular TNC . . . .”

71

TNCs must file a photograph of this trade dress

with the CPUC’s Safety and Enforcement Division.

72

As a result of these new

regulations, the “visual representations” factor may tilt in favor of an employer-

employee relationship. However, the TNC signage may be much less

noticeable than taxicab or trucking company vehicles that have distinctive

colors and logos written in prominent, large letters. And visual displays are far

from dispositive evidence of an employment relationship.

73

b. Accountability to Dispatcher

The element of control would be further strengthened by a finding that

drivers are required to maintain communication with the transportation

company’s dispatcher and can be punished for failure to follow orders or not

work at specific times.

74

It is tricky to apply this factor to TNCs. On the one

69. Uber, for example, allows uberX drivers to use their own cars and has no specific

requirements for color or labeling. Vehicle Requirements, UBER, http://www.driveubernyc.com/cars

[http://perma.cc/J7NW-WJRM] (last visited Oct. 13, 2015).

70. 2013 CPUC Order, supra note 35, at 18.

71. Id.

72. Id.

73. See, e.g., Holmes v. United Indep. Taxi, No. B149582, 2002 WL 228197, at 2 (Cal. Ct.

App. Feb. 15, 2002) (finding a driver to be an independent contractor, rather than an employee, even

though the company required the driver to display a sign in the right lower corner of his car’s

windshield while transporting conventioneers). Plaintiffs could also potentially sue under a theory of

estoppel. Bremer, supra note 54, § 4 (“[I]f the injured party was a passenger in the taxicab, proof that

the target company held itself out as the operator of the taxicab may estop the company from denying

the agency of the driver.

The two elements necessary to establish this estoppel are a holding out by the

target company and a justifiable reliance on it by the injured party.”). A Lyft customer, for example,

might reasonably and non-negligently rely on a Lyft vehicle’s distinctive branding as a sign that the

company is in control of its drivers and responsible for passenger safety. Especially in a hit-and-run

scenario, if a bystander could identify Lyft as the operator, but not the specific driver, Lyft could

potentially be liable for injuries. See, e.g., Ass’n of Indep. Taxi Operators v. Kern, 13 A.2d 374, 376–

77 (Md. 1940) (holding that when an unidentified driver perpetrated a hit-and-run in a taxicab

identifiable to one company, the company could be held liable to the victim). This argument is set to

suffer, though, as Lyft is phasing out its comically oversized and very visible fluffy pink moustache

for a smaller, less noticeable glowing pink dashboard ornament. Vanhemert, supra note 68.

74. Yellow Cab Coop., Inc. v. Workers’ Comp. Appeals Bd., 277 Cal. Rptr. 434, 441 (Ct.

App. 1991) (finding the necessary element of control where drivers were extensively monitored by

radio communications and punished for not accepting radio orders); People v. Rouse, 249 Cal. Rptr.

281, 284 (App. Dep’t Super. Ct. 1988) (noting that a driver’s consistent checking in with his

dispatcher by radio, along with sanctions for refusal to accept rides referred by the dispatcher led to a

“reasonable inference” that the driver was an employee); Bremer, supra note 54, § 7 (“Of particular

importance is whether the driver was required to respond to calls; if he was, whether by virtue of

contract, lease, association rules, or by custom, then the target company had that kind of control

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 247

hand, drivers do not verbally communicate with TNC operators, or any

superior at all, during the normal course of business; their only interaction is

with the TNC phone application.

75

On the other hand, drivers are constantly in

virtual communication with TNCs when they are logged into the app, which

tracks things like driver ratings, ride acceptance rates, and vehicle location.

76

One could reasonably conclude that this level of control is actually stronger

than a taxicab company requiring its drivers to periodically radio into a

dispatcher. And at least one TNC, uberX, threatened to sanction drivers who do

not maintain minimum ratings from passengers or who refuse too many ride

requests, an indication that drivers are highly accountable to the company.

77

Even so, the weight of these considerations is diminished by the fact that

drivers are never actually required to work or call into a TNC dispatcher; nor

are they required to accept specific rides.

78

Courts are therefore unlikely to find

that this factor—GPS tracking and minimum quality standards—rises to the

level of control exercised by traditional transportation dispatchers who

communicate directly with drivers and relay affirmative demands.

c. Vehicle Ownership

The vehicle ownership factor is relatively straightforward: TNC drivers

generally use their own cars,

79

and this will serve as evidence that they are not

employees.

80

And drivers, not the TNCs, are responsible for vehicle

maintenance and fueling costs.

81

The analysis may become slightly more

complicated in light of Uber’s recent move to facilitate lease agreements

between manufacturers and prospective drivers.

82

But even this arrangement

does not change the simple fact that drivers, not Uber, lease the vehicles. Thus,

this factor tilts heavily in favor of TNCs.

generally found to evidence agency. On the other hand, if the driver was free to accept or reject any

call then the fact that dispatching services were provided is less significant.”).

75. Uber, for example, automatically assigns drivers to passengers based on algorithms

tracking driver locations. Voytek, Optimizing a Dispatch System Using an AI Simulation Framework,

UBER (Apr. 11, 2014), http://blog.uber.com/aisimulation [http://perma.cc/5D9R-5CNK].

76. James Cook, Uber’s Internal Charts Show How its Driver-Rating System Actually Works,

BUS. INSIDER (Feb. 11, 2015), http://www.businessinsider.com/leaked-charts-show-how-ubers-driver-

rating-system-works-2015-2 [http://perma.cc/GUY4-QXKW].

77. Id.

78. See Uber NYE Answer, supra note 56, at 2.

79. Ryan Lawler, Uber Study Shows Its Drivers Make More Per Hour and Work Fewer Hours

than Taxi Drivers, TECHCRUNCH (Jan. 22, 2015), http://techcrunch.com/2015/01/22/uber-study

[http://perma.cc/2MRU-LFNG].

80. See People v. Rouse, 249 Cal. Rptr. 281, 284 (App. Dep’t Super. Ct. 1988).

81. Id.

82. Ken Bensinger & Johana Bhuiyan, Flouting Law, Uber Suspends Drivers for Properly

Registering Cars, BUZZFEED (Jan. 22, 2015), http://www.buzzfeed.com/kenbensinger/ubers-auto-

registration-gambit [http://perma.cc/BVU6-2M3J]. The company has reportedly even directed some of

the drivers participating in its car purchase and lease finance programs to register their new cars as

personal vehicles rather than commercial ones and has temporarily suspended some driver accounts

whose cars were registered as commercial vehicles. Id.

248 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

d. Non-Competes and Other Contractual Provisions

Courts may also find drivers to be employees of transportation companies

based on the actual terms by which they have agreed to operate. For example,

one court found that a taxi company forcing drivers not to work for any other

companies served as the “most significant” factor in determining that the driver

was an employee.

83

Likewise, TNCs sometimes prohibit drivers from operating

for other services,

84

evidence that weighs in favor of finding an employer-

employee relationship.

On the other hand, TNCs may explicitly require drivers to acknowledge

that they operate as independent contractors, not employees, as a condition of

using the services. According to Uber, the driver in the New Year’s Eve

accident entered into contracts with the company that declared his status as an

“independent, for-hire transportation provider” for uberX and an “independent

contractor” of Uber’s subsidiary, Raiser, LLC.

85

The agreement’s language,

assuming it is standard for Uber and other TNCs, weighs in favor of a court

finding that TNC drivers are indeed independent contractors.

86

83. Yellow Cab Coop., Inc. v. Workers’ Comp. Appeals Bd., 277 Cal. Rptr. 434, 441 (Ct.

App. 1991).

84. In New York, for example, Uber sent drivers text messages that they could be deactivated

(effectively fired) if they did “trips with a base” their “vehicle [isn’t] affiliated with,” and even went so

far as to call at least one driver and tell him he could not work for Uber unless he terminated his

relationship with competitor Lyft. Erica Fink, Uber Threatens Drivers: Do Not Work for Lyft, CNN

(Aug. 5, 2014), http://money.cnn.com/2014/08/04/technology/uber-lyft [http://perma.cc/N3Z6-5BBJ].

Limiting an agent’s freedom to contract elsewhere in this manner has weighed significantly in finding

an employment relationship in the context of workers’ compensation. See Yellow Cab, 277 Cal. Rptr.

at 441. This consideration may be a moot point in California, though, where non-compete clauses are

strongly disfavored by both the legislature and the courts. See Scott v. Snelling & Snelling, Inc., 732 F.

Supp. 1034, 1042–43 (N.D. Cal. 1990); D’sa v. Playhut, Inc., 85 Cal. App. 4th 927, 933 (2000).

85. Uber NYE Answer, supra note 56, at 4. Likewise, in their public statements and terms of

service, none of the TNC companies ever refer to drivers as “employees.” Uber’s website formerly

characterized its drivers as “independent contractors”; this page was removed from Uber’s website at

some point after December 4, 2014. See Who Are The Drivers On The Uber System?, UBER,

[https://web.archive.org/web/20140524143041/http://support.uber.com/hc/en-us/articles/201955457-

Who-are-the-drivers-on-the-Uber-system-] (archived May 24, 2014 and last visited Dec. 4, 2014).

Sidecar explains that drivers are not employees but rather “independent workers who voluntarily use

our mobile platform to be matched with passengers and obtain payment cashlessly through the app.”

Terms of Services, SIDECAR, supra note 33. The company elaborates on the relationship: “It is up to

the driver to decide when he or she wishes to drive using the sidecar app, whether or not to offer a ride

to a passenger contacted through the sidecar platform, and what pricing adjustment the driver wishes

to set.” Id. Lyft, on the other hand, does not explicitly label its drivers, but the company’s Terms of

Service still maintains that the company “has no responsibility whatsoever for the actions or conduct

of drivers or riders.” Lyft Terms of Service, LYFT, supra note 33.

86. See, e.g., Lopez v. El Palmar Taxi, Inc., 676 S.E.2d 460, 464 (Ga. App. 2009) (“The

evidence does not show that El Palmar assumed control over the time, manner or method of Julaju’s

work. He was free to work when and for as long as he wanted, he was not required to accept fares

from El Palmar, he could obtain his own fares and he could work anywhere the taxi could legally be

operated. The fact that the cars he drove displayed the El Palmar logo and the fact that he received

calls from El Palmar are not sufficient to create an employer-employee relationship.”); Asplund v.

Selected Invs. in Fin. Equities, Inc., 103 Cal. Rptr. 2d 34, 49 (Ct. App. 2000) (“[T]he limitations set

forth in the sales representatives agreement, coupled with the absence of substantial evidence of

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 249

e. Termination

Finally, the right to terminate workers without cause can serve as

evidence of an employee-employer relationship.

87

This factor should weigh

slightly, though not dispositively, in favor of finding drivers to be independent

contractors. Uber, for example, reserves broad power to terminate its

relationship with drivers, but this power is limited to situations when “the

Transportation Company or its Drivers fail to maintain the standards of

appearance and service required by the users of the Uber Software.”

88

Such

qualifications, coupled with the fact that Uber’s employment agreement

contains an arbitration clause,

89

could serve to support the company’s claim

that drivers are independent contractors.

90

***

Ultimately, the weighing of employment factors is a murky endeavor.

Plaintiffs have had, and may continue to have, some success in arguing that

drivers are employees of TNCs, as discussed in the next Subsection; yet relying

on such an

argument is risky given the subjectivity and intensely fact-specific

nature of the employer-control test.

apparent or actual authority beyond that specified in the agreement, eliminates any basis upon which to

impose vicarious liability on [the defendant] under the doctrine of respondeat superior.”). An

agreement, though, is far from dispositive. See B.E. WITKIN, 2 WITKIN, SUMMARY WORKERS’ COMP,

§ 189, at 772 (10th ed., 2005) (“Signing the agreement to forgo coverage as an independent contractor

is significant but not controlling where compelling indicia of employment are otherwise present.”).

Plaintiffs could argue, however, that the contractual language declaring drivers to be independent

contractors is meaningless when the drivers are working solely for one TNC and therefore are not

freely contracting their services. This argument has been persuasive in the real estate agent and broker

relationship. See Reagan v. Keller Williams Realty, Inc., No. B192890, 2007 WL 2447021, at 10 (Cal.

Ct. App. 2007) (“[F]or purposes of tort liability, a real estate agent-broker relationship may not be

characterized as that of an independent contractor when the salesperson is acting within the scope of

employment . . . Insofar as liability to a third party is concerned, any provision purporting to change

the relationship from agent to independent contractor is invalid.”); Gipson v. Davis Realty Co., 30 Cal.

Rptr. 253, 262 (Dist. Ct. App. 1963) (finding, based on statutory provisions, that because a real estate

salesmen “can act only for, on behalf of, and in place of the broker under whom he is licensed, and that

his acts are limited to those which he does and performs,” the agent cannot be classified as an

independent contractor and “any contract which purports to change that relationship from that of agent

to independent contractor is invalid as being contrary to the provisions of the Real Estate Law”).

87. See Alexander v. FedEx Ground Package Sys., Inc., 765 F.3d 981, 988 (9th Cir. 2014)

(“The right to terminate at will, without cause, is ‘[s]trong evidence in support of an employment

relationship.’” (citations omitted)); Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc. v. Superior Court, 269 Cal. Rptr.

647, 653 (Ct. App. 1990), modified (June 5, 1990) (“Perhaps no single circumstance is more

conclusive to show the relationship of an employee than the right of the employer to end the service

whenever he sees fit to do so.”).

88. Uber Software License and Online Services Agreement at 5, O’Conner v. Uber Techs.,

Inc., No. 3:13-cv-03826-EMC (N.D. Cal Aug. 3, 2015) (on file with author).

89. Id. at 11.

90. See Alexander, 765 F.3d at 994 (“The first factor, the right to terminate at will, slightly

favors FedEx. The OA contains an arbitration clause and does not give FedEx an unqualified right to

terminate.”).

250 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

3. Driver Victories over TNCs

Though not yet heavily litigated, at least two plaintiffs have prevailed in

showing an employment relationship between TNCs and drivers. But these

cases have both been in the context of employment benefits, not tort liability.

91

And the decisions have merely symbolic—not precedential—value; they apply

only to the single drivers seeking benefits in each case.

92

In Florida, the

Department of Economic Opportunity (DEO) found that one driver, who had

been laid off by Uber, was entitled to collect unemployment benefits because

he had been an employee, not an independent contractor, of the company.

93

Soon after the Florida decision, another Uber driver, appearing pro per,

94

successfully convinced the California Labor Commissioner that she was an

employee of Uber.

95

As a result, the Commissioner awarded the employee

reimbursement of labor expenses plus interest, a total of $4,152.20.

96

Although

the ruling applies only to the single driver who brought the suit, the

Commissioner’s in-depth analysis of Uber’s operations and its control over

drivers

97

could provide a template for finding that all TNC drivers are

employees. In coming to a decision, the Commissioner analyzed a number of

factors that could also apply to respondeat superior liability, including Uber’s

extensive driver vetting procedures, the company’s control over the “tools”

(vehicles) drivers use, and Uber’s authority to set rates for the service.

98

TNCs should be nervous that the California decision might influence

future analyses of their employment relationships with drivers. The distinction

between independent contractors and employees could have far-reaching costs

for TNCs beyond simply creating tort liability; one report from the National

Employment Law Project estimated that re-categorizing drivers could cost the

companies an additional 30 percent in labor costs.

99

Faced with such a dire—

91. Mike Isaac & Natasha Singer, California Says Uber Driver is Employee, Not a

Contractor, N.Y. TIMES (June 17, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/18/business/uber-contests-

california-labor-ruling-that-says-drivers-should-be-employees.html [http://perma.cc/6YL5-NHZ2].

92. Id.

93. Johana Bhuiyan, Florida Agency Classifies Uber Driver as Employee, Says He Is Eligible

for Unemployment, BUZZFEED (May 22, 2015), http://www.buzzfeed.com/johanabhuiyan/florida-

agency-classifies-uber-driver-as-employee-says-he-is [http://perma.cc/95W9-TQUE].

94. Berwick v. Uber Techs., Inc., No. 11-46739 EK, 2015 WL 4153765, at *1 (Cal. Dept.

Labor June 3, 2015).

95. Id. at *10.

96. Id. at *11.

97. See id. at *9.

98. Id.

99. Ben Popper, Making Drivers Into Employees, Not Contractors, Could Hurt Uber’s

Business, VERGE (June 17, 2015), http://www.theverge.com/2015/6/17/8797021/uber-california-

lawsuit-labor-employee-contractor [http://perma.cc/32ZG-6KEA]; see also People ex rel. Harris v. Pac

Anchor Transp., Inc., 329 P.3d 180, 183 (Cal. 2014), cert. denied, 135 S. Ct. 1400 (2015) (recognizing

a number of requirements unique to the employer-employee relationship: “(1) pay unemployment

insurance taxes . . . ; (2) pay employment training fund taxes . . . ; (3) withhold state disability

insurance taxes . . . ; (4) withhold state income taxes . . . ; (5) provide worker’s compensation . . . ;

(6) provide employees with itemized written wage statements . . . and provide employees with certain

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 251

and potentially even existential—threat, TNCs have begun expending

significant resources to maintain the status quo. Uber has already appealed both

the California and Florida decisions,

100

and the company is fighting similar

issues “on multiple fronts across the country.”

101

And even though the narrow

decisions in California and Florida could be a sign of future trouble for Uber

and other TNCs, at least five other states have gone the opposite direction and

accepted Uber’s argument that drivers are independent contractors.

102

TNCs are also undertaking major lobbying efforts, which could burnish

public and legislative support and ultimately lead to greater statutory

protections for the companies. Uber, for example, now employs 250 lobbyists

and twenty-nine lobbying firms in state capitals around the nation—and these

figures do not even count the company’s many lobbyists at the municipal

level.

103

The companies do not look to be exhausting their war chests any time

soon: Uber has attracted billions in private financing, bringing its valuation to

over $50 billion,

104

and Lyft recently received $100 million in financing from

legendary investor Carl Icahn.

105

And TNCs enjoy widespread support among

consumers. For example, Uber received nearly a million signatures on petitions

supporting the company.

106

In other words, TNCs have the political clout and resources to make sure

that plaintiffs will not easily prevail in any battle over categorizing drivers as

employees.

Lastly, the issue is not static: although some or even most courts might

find an employer-employee relationship based on TNCs’ current arrangements,

these nimble, well-financed companies have the means to adapt to and

circumvent employer-specific regulations. Uber, for example, has already

records that California’s Industrial Welfare Commission wage order No. 9–2001, section 7,

requires . . . ; (7) reimburse employees for business expenses and losses . . . ; and (8) ensure payment at

all times of California’s minimum wage”).

100. Celia Ampel, Uber Appeals State’s Treatment of Drivers as Employees, DAILY BUS. REV.

(June 29, 2015), http://www.dailybusinessreview.com/id=1202730834966/Uber-Appeals-States-

Treatment-of-Drivers-as-Employees?slreturn=20150620124626 [http://perma.cc/K5X2-G8W8]; Isaac

& Singer, supra note 91.

101. Douglas Hanks, For Uber, Loyal Drivers and a New Fight for Benefits, MIAMI HERALD

(May 21, 2015), http://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/article21599697.html [http://perma.cc

/ZCW9-F9LV].

102. Isaac & Singer, supra note 91.

103. Karen Weise, This Is How Uber Takes Over a City, BLOOMBERG BUSINESS (June 23,

2015), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2015-06-23/this-is-how-uber-takes-over-a-city

[http://perma.cc/T7KC-MM5S]. In Portland, Oregon, alone, the company deployed at least ten people

to lobby on its behalf in a recent battle to enter the city—a battle that Uber ultimately won. Id.

104. Pui-Wing Tam & Michael J. de la Merced, Uber Fund-Raising Points to $50 Billion

Valuation, N.Y. TIMES (May 9, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/09/technology/uber-fund-

raising-points-to-50-billion-valuation.html [http://perma.cc/5D79-5RCD].

105. Mike Isaac & Alexandra Stevenson, Carl Icahn Invests $100 Million in Lyft, N.Y. TIMES

(May 15, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/16/technology/carl-icahn-invests-100-million-in-

lyft.html [http://perma.cc/4HPQ-83CD].

106. Weise, supra note 103.

252 CALIFORNIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 104:233

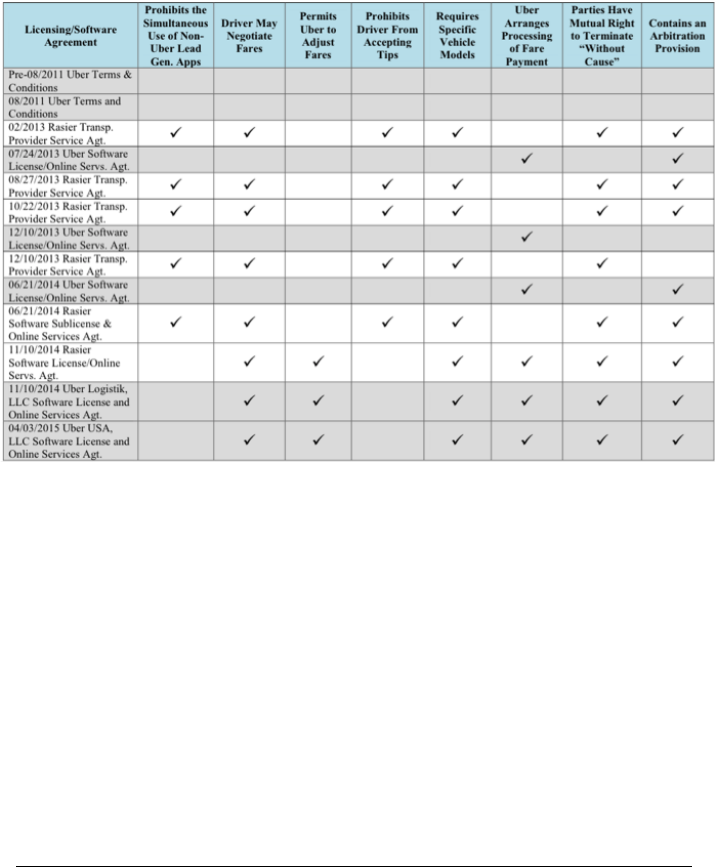

shown great flexibility in modifying contractual arrangements with drivers, as

illustrated by a chart the company submitted in opposition to certifying a class

of drivers

107

:

Uber used this chart to argue that drivers were not similarly situated

and therefore no individual plaintiff could represent the class.

108

But the chart

also shows the potential ease with which TNCs could skirt the employer-

employee relationship: with courts weighing a multitude of factors to determine

the existence of an employment relationship, TNCs can and likely will make

marginal tweaks to their contracts in the hopes of ever-so-slightly tilting the

scales in their favor.

II.

THE PROMISE OF THE NONDELEGABLE DUTY DOCTRINE

TNCs have had little success arguing that they are mere platforms for

connecting buyers and sellers. And although a few drivers have succeeded in

obtaining employment benefits from TNCs, the separate question whether

107. Amended Ex. 41, O’Conner v. Uber Techs., Inc., No. 3:13-cv-03826-EMC (N.D. Cal

Aug. 3, 2015) (on file with author).

108. Davey Alba, Judge: California Drivers Can Go Class-Action to Sue Uber, WIRED (Sept.

1, 2015), http://www.wired.com/2015/09/judge-california-drivers-can-go-class-action-sue-uber

[http://perma.cc/2L9S-76E8]. Uber failed to persuade the judge, who ultimately certified the class on

the question of employment classification. Amended Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Class Certification, O’Conner v. Uber Techs., Inc., No. 3:13-cv-03826-EMC

(N.D. Cal. Sept. 1, 2015).

2016] WHEN “DISRUPTION” COLLIDES WITH ACCOUNTABILITY 253

drivers are employees of TNCs for liability purposes remains unsettled. Amid

so much uncertainty, this Note proposes a means of holding TNCs liable that

will recognize their unique employment structure while also confronting the

not-so-unique dangers that TNC services pose to passengers and bystanders.

Rather than relying exclusively on respondeat superior, plaintiffs may be

better served by arguing an alternative route to liability—that in the absence of

an employee-employer relationship, TNCs are liable for their drivers because

they have a nondelegable duty to operate safely.

In general, an employer cannot be held liable for the acts of an

independent contractor.

109

This is likely one of the reasons that TNCs have

gone out of their way to describe their drivers as “independent.”

110

But the rule

is not absolute; it is limited by public policy concerns.

111

The nondelegable

duty rule alleviates the problem of entities contracting away their rightful

responsibilities: a company cannot avoid liability by delegating work to an

independent contractor when it is publicly licensed or franchised and its work

presents a safety concern to the public.

112

Courts sometimes break the nondelegable duty rule into two disjunctive

parts, either of which can create a nondelegable duty: (1) where a company is

liable when it is subject to public franchise, or (2) where a company undertakes

an activity that is inherently dangerous to others.

113

But California courts

frequently conflate these two criteria based on a pragmatic rationale: “The

effectiveness of safety regulations is necessarily impaired if a carrier conducts

its business by engaging independent contractors over whom it exercises no

control.”

114

109. B.E. WITKIN, 6 WITKIN, SUMMARY TORTS § 1253, at 642 (10th ed., 2005) (noting “the

general rule of nonliability for negligence of an independent contractor”).

110. There are in fact a host of additional costs that come from re-categorizing workers as

employees rather than independent contractors; the National Employment Law Project estimated that

making the switch could amount to an additional 30 percent in labor costs for ridesharing companies.

Popper, supra note 99; see also People ex rel. Harris v. Pac Anchor Transp., Inc., 329 P.3d 180, 183

(Cal. 2014), cert. denied, 135 S. Ct. 1400 (2015) (as quoted supra note 99).

111. Barry v. Raskov, 283 Cal. Rptr. 463, 467 (Ct. App. 1991).

112. 6 WITKIN, SUMMARY TORTS, supra note 109, § 1247, at 634, 636, 642. The rule is

grounded in a sense of fairness. See Maloney v. Rath, 445 P.2d 513, 515 (Cal. 1968) (“To the extent

that recognition of nondelegable duties tends to insure that there will be financially responsible

defendant available to compensate for the negligent harms caused by that defendant’s activity, it

ameliorates the need for strict liability to secure compensation.”).