Report 07-2013 POLICY BRIEF May 2013

INSTITUTE of PUBLIC POLICY

Harry S Truman School of Public Affairs

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and

Surrounding States

Judith Stallmann, Andrew Wesemann and David Valentine

Introduction

States and communities have pursued economic development strategies for

over 30 years but little is known about the overall effectiveness of those

strategies. All states are concerned with jobs and economic development,

particularly in times of economic downturn, and overall taxes are

frequently a part of the discussion of strategies to improve a state’s

competitive position. Several states reduced individual income tax rates in

the early 2000s to spur spending and economic growth, and both Kansas

and Nebraska did the same in 2012. Kansas reduced its individual tax rates

and cut non-wage income taxes for some corporations—mainly small

businesses—explicitly to spur economic development in the state and cut

the size of government (Peters, 2012). Although the impact of these

changes on the Kansas economy, and on the ability of the state to fund state

Talking Points

Taxes paid are a combination of the tax rate and the tax base.

Comparing just tax rates, as is commonly done, ignores important

differences in tax bases that affect the total taxes paid.

This report uses effective tax rates to adjust for differences in bases.

Several methods that are used to calculate effective tax rates are

reviewed: hypothetical firm analysis (Tables 1, 2 and 3), business taxes

as a percentage of private gross state product (Graph 1), taxes per capita

and taxes per $1000 of personal income (Table 4).

This paper compares Missouri and its neighbors. On the measures of

effective tax rates reviewed, Missouri ranks as a middle or low tax state

in comparison with its neighbors (Table 5).

Taxes are but one of many factors, such as labor and other input costs,

that enter into a firm’s decision making. In addition, the use of tax

revenues to fund infrastructure, public safety and education are

examples of expenditures that firms rely on to lower their costs.

Dr. Judith Stallmann is a

Professor of Agricultural

and Applied Economics,

Rural Sociology and Public

Affairs Community

Development Extension

Specialist at the University

of Missouri

Andrew Wesemann is a

Doctoral Candidate,

Truman School of Public

Affairs, University of

Missouri

Dr. David Valentine is a

Senior Research Fellow in

the Institute of Public

Policy, Truman School of

Public Affairs, University

of Missouri

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

2

programs is unclear, Kansas’ action has triggered a discussion about taxes and economic

development in Missouri and other states bordering Kansas.

This brief summarizes studies of several measures of taxation in Missouri and the eight

surrounding states under the assumption that multiple measures will provide more reliable

indicators of a state’s overall tax policy. However, numerous other factors influence a state’s

economic growth and therefore studies that rely solely on taxes provide an incomplete portrayal

of state conditions.

A Word on Methodology

This report summarizes existing analyses and data sources that use a variety of measures to

present cross-state comparisons. Those involved in economic development policy typically use

just one measure, the one that is the most advantageous to their position, to demonstrate the

value of, or detrimental effects of proposed economic development strategies. There is

significant variability in the measures used and any single measure in isolation can produce

misleading conclusions about a state’s taxes. To compensate for this problem, we rank the states

using multiple measures. We can gain confidence in the results when these measures are

reasonably consistent for states used in the comparison.

Before proceeding, however, it is important to note that cross-state comparisons of taxes are

fraught with difficulty. For example, discussions of taxes often begin with a discussion of tax

rates but taxes paid are a combination of the tax rates and the tax base. The tax base defines

what is taxed and the tax rate defines by how much the base is taxed. Often there are exemptions

from a base and those exemptions, which vary by state, affect the size of the base and the actual

taxes paid. Given these issues, one common alternative is to calculate an effective tax rate. This

begins by taking the broadest definition of the base that is used and comparing all other bases to

it. For example, a corporation without any tax incentives has a broader base than a firm with

incentives. Though each may pay the same official tax rate the first firm has a higher effective

rate than the latter because it has a larger base.

We review several recent studies which use the most common methods of estimating effective

tax rates. We first examine effective tax rates drawing on hypothetical firm analyses, a tool used

by economists to simplify and standardize cross-state comparisons. These comparisons enable

us to estimate the level of taxation on businesses, including mature and new firms, and rank each

of the nine states on each measure. We also examine business taxes as a percentage of private

gross state product. Finally, we examine per capita taxes and taxes per $1,000 of personal

income as measures of tax policy in the states. We use these measures to rank the nine states

considered in this analysis. We recognize that taxes are only a part of the economic development

picture. We return to this point in the conclusion.

Assessing Effective Tax Rates Using a Hypothetical Firm Analysis

One method to compare effective tax rates across states is to construct a hypothetical or

representative firm and apply the existing tax laws of each state to the firm and compare the

calculated tax rate or the after-tax rate of return. As the term “hypothetical” indicates, the firm is

simplified to its most important aspects, rather than using all of its details. In addition, state tax

systems are simplified, usually by focusing on the major taxes paid by the majority of firms.

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

3

Two recent national studies use this approach, describing representative firms in several sectors

and then applying the tax laws of the state. The first was conducted by Ernst & Young (2011)

and the second was produced by the Tax Foundation (2012). Each study has its own focus and

its own set of assumptions (see Appendix A for a comparison of the assumptions). It should be

pointed out that these studies are representative only of the types of firms included and not

business taxes for the entire state.

Ernst & Young (2011) focuses on investment by new firms and calculates the 30-year average

effective tax rate for that firm beginning with tax year 2009. Five types of firms were selected

specifically because of their mobility—headquarters, research and development, office and

career center, and both durable and non-durable manufacturing. The financial characteristics of

each type of firm were held constant across states to isolate the effect of taxes. The taxes

included were corporate income, franchise and gross receipts taxes; sales and use taxes on

business purchases; and property taxes (see Appendix A for more detail). The Ernst & Young

effective tax rates for Missouri and the surrounding states are presented in Table 1. Using the

Ernst & Young measure, Illinois, Iowa and Kentucky have the lowest effective tax rates,

Nebraska, Tennessee and Kansas have the highest, and Missouri falls in the middle third.

TABLE 1: ERNST AND YOUNG OVERALL EFFECTIVE TAX RATES FOR A

30-YEAR INVESTMENT BEGINNING IN 2009 FOR HYPOTHETICAL FIRMS

1

*

(Weighted by capital investment)

State

Effective Tax Tate

State Rank

Arkansas

8.9%

6

Illinois

4.6%

1

Iowa

6.4%

2

Kansas

11.2%

9

Kentucky

6.5%

3

Missouri

7.1%

4

Nebraska

9.4%

7

Oklahoma

8.8%

5

Tennessee

10.3%

8

*1 is the lowest rank and indicates the lowest tax level.

Source: Ernst & Young (2011), Table 2, p. 9.

Based on tax law as of April, 2011, the Tax Foundation (2012) conducted a hypothetical firm

analysis for seven types of mobile firms—corporate headquarters, research and development

center, capital-intensive manufacturing, labor-intensive manufacturing, call center, distribution

center, and retail store. The firms were divided into categories based on the likelihood that they

would locate in a large city (corporate headquarters, call center and retail store) or mid-sized city

(the other types of firms), because these factors affect their local taxes. For Missouri the major

city is St. Louis and the mid-sized city is Joplin. As with the Ernst & Young (2011) study, all

firms are corporations, that is, they are taxpaying rather than tax pass-through entities.

1

Data on Kansas taxes presented throughout this report do not reflect the 2012 tax changes.

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

4

The effective tax rate is based on corporate income, capital stock, unemployment, sales,

property, gross receipts and inventory taxes. Effective rates are calculated for mature firms (10

years or older) and new firms (3 years or less) since new firms may be able to take advantage of

tax incentives—new job credits and new hire withholding rebates, investment tax credits, R&D

credits, property tax abatements, exemptions for sales taxes on equipment, depreciation of

buildings and personal property (Tax Foundation, 2012). The national average tax is given a

score of 100 and the score for each state is their percentage relative to the national average.

TABLE 2: TAX FOUNDATION STATE TAX INDEX FOR 2011: OVERALL EFFECTIVE

TAX RATE AS A PERCENTAGE OF THE NATIONAL AVERAGE TAX RATE*

State

Mature

Firm Index

Mature

Firm Rank

New Firm

Index

New Firm

Rank

Arkansas

102.8

5

69.6

4

Illinois

126.4

8

94.2

5

Iowa

116.5

7

126.8

8

Kansas

133.5

9

141.6

9

Kentucky

88.4

3

69.4

3

Missouri

108.8

6

97.0

6

Nebraska

82.5

1

31.7

1

Oklahoma

87.1

2

65.3

2

Tennessee

101.3

4

108.7

7

*Lowest rank indicates lowest tax index score; 1=lowest taxes.

Source: Tax Foundation (2012), Table 7, p. 14.

Table 2 indicates how each of the nine states’ effective tax rates affect mature and new

hypothetical firms and compares those rates to the national average. Only Nebraska, Oklahoma

and Kentucky have overall tax rates that are lower than the national average for mature firms

while six of the nine states, including Missouri, tax mature firms at a higher rate than the national

average. Alternatively, six of the states have tax rates for new firms that are lower than the

national average. Iowa, Kansas and Tennessee have tax rates for new firms higher than the

national average. The mature and new firm rankings for seven of the nine states, including

Missouri, are similar across both measures.

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

5

TABLE 3: RANKINGS FROM THE HYPOTHETICAL FIRM ANALYSES*

State

Ernst & Young

Rank

Tax Foundation

Mature Firm Rank

Tax Foundation

New Firm Rank

Arkansas

6

5

4

Illinois

1

8

5

Iowa

2

7

8

Kansas

9

9

9

Kentucky

3

3

3

Missouri

4

6

6

Nebraska

7

1

1

Oklahoma

5

2

2

Tennessee

8

4

7

*1 is the lowest rank and indicates the lowest effective tax rate (Ernst & Young) and the lowest tax

index score (Tax Foundation).

Source: Ernst & Young (2011), Table 2, p. 9; Tax Foundation (2012), Table 7, p. 14.

Table 3 presents the state rankings from the two hypothetical firm studies to demonstrate the

range of results for each of the nine states. Some states have relatively little variation across the

three measures, including Arkansas, Kansas, Kentucky, and Missouri. Most of these states,

including Missouri, have fairly consistent “middling” rankings. Only Kentucky and Kansas have

the same rank on all three measures. Kentucky ranks third lowest and Kansas ranks highest.

Now consider the states where the variation is wider, such as Illinois, Iowa and Nebraska. Here,

the conclusions that one might draw depend upon which study is examined. Put differently,

states may appear more or less attractive to firms in terms of effective tax rates that are produced

by the hypothetical firm calculations. Consequently, it is important to proceed with caution

when making conclusions regarding state effective tax rates because each study makes different

assumptions about the firm and the state (see Appendix A). In these hypothetical firm studies, as

in all economic development studies, the assumptions can critically influence the findings. For

example, effective tax rates are likely higher in the Tax Foundation study because it includes

sales taxes charged to consumers. It should also be noted that the analysis applies only to the

types of firms studied and, in the case of Tax Foundation study, to the particular cities chosen

within each state.

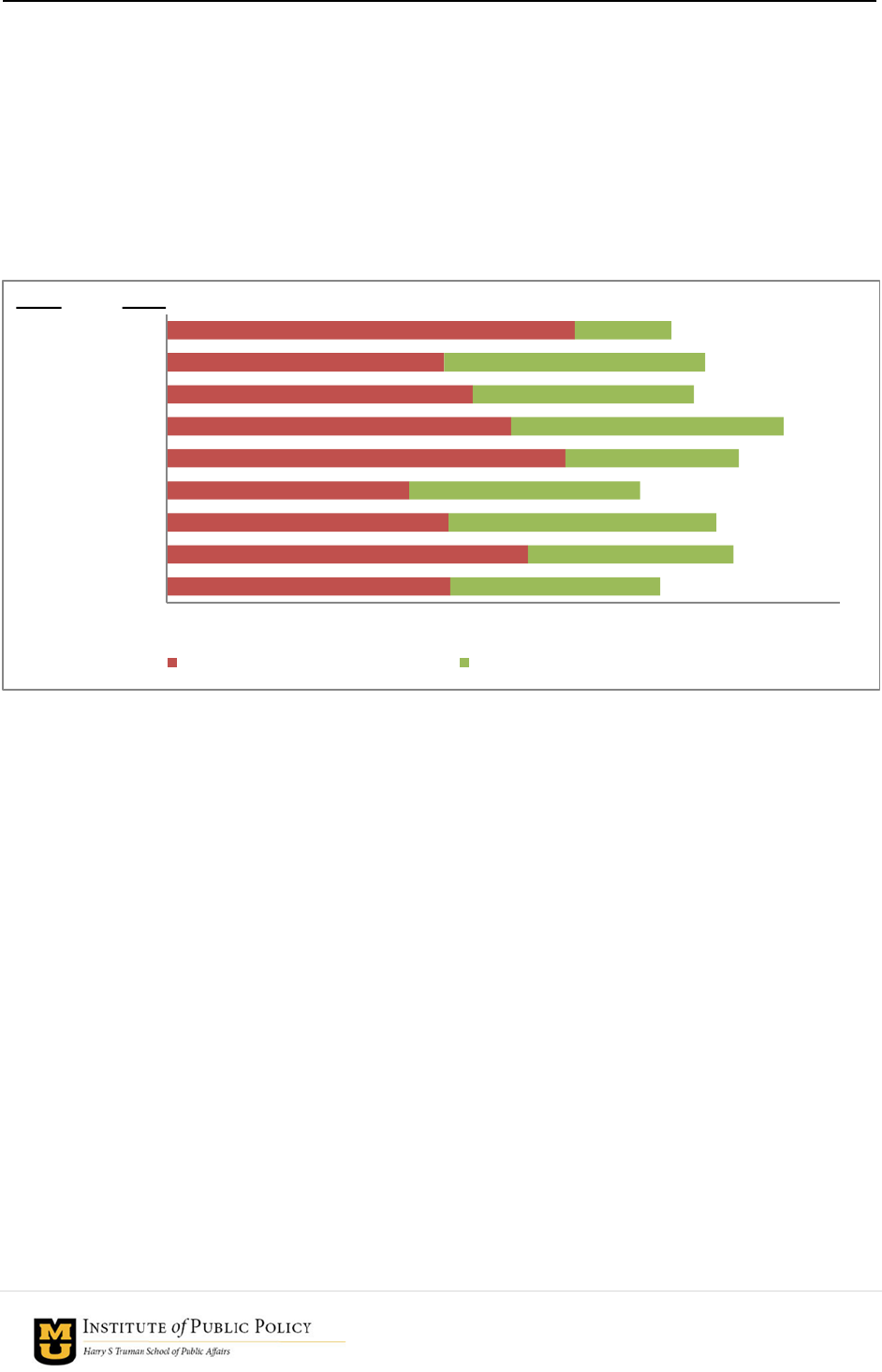

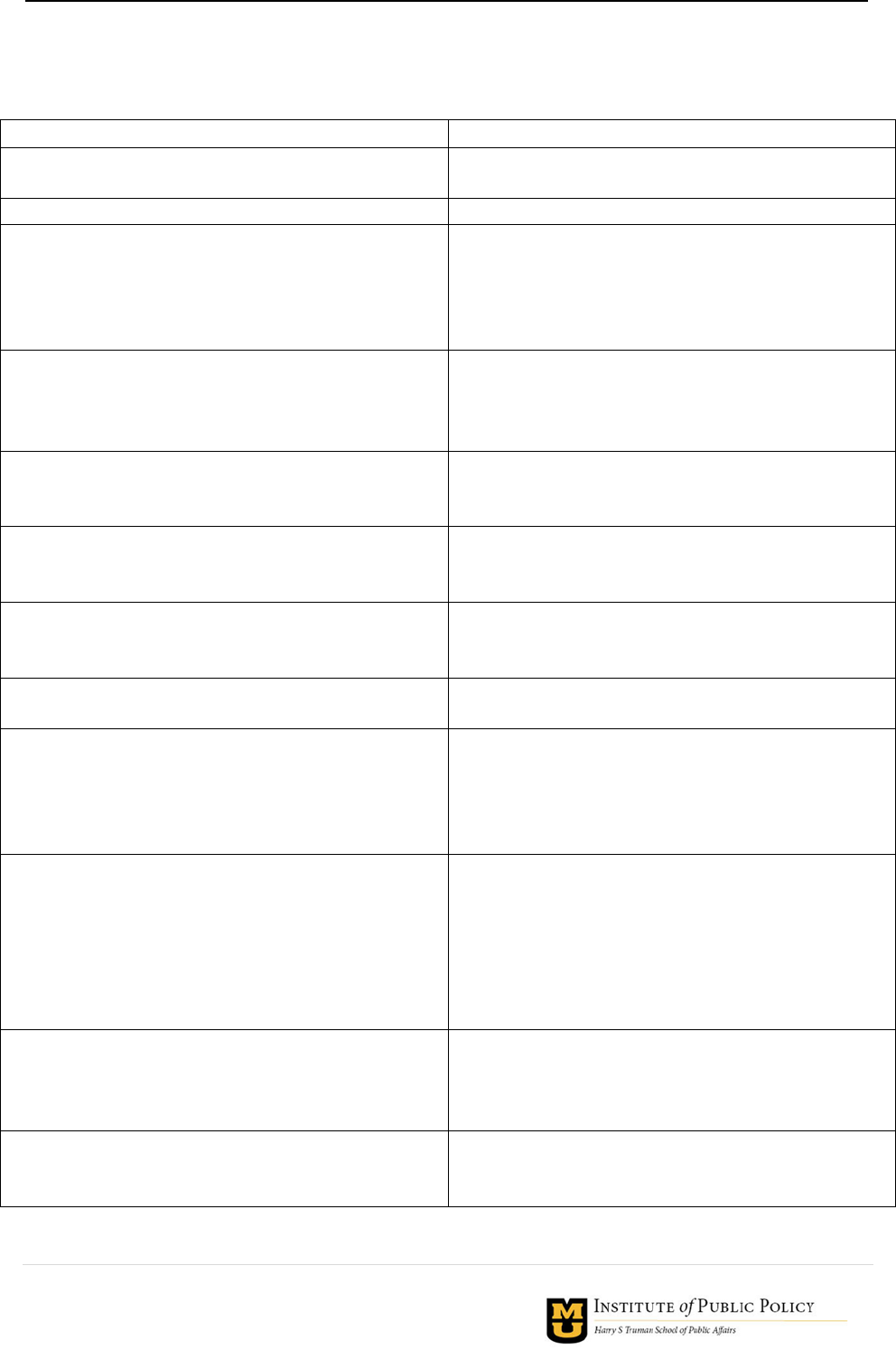

Business Taxes as a Percentage of Private Gross State Product

An alternative to calculating effective tax rates through hypothetical firm analyses is to use

business taxes as a percentage of value added by firms in the state, the private gross state

product. Ernst & Young (2012) use this approach to calculate an average tax rate per dollar of

value added in each state. The taxes include “business property taxes, sales and excise taxes paid

by businesses on their input purchases, gross receipts taxes, corporate income and franchise

taxes, business and corporate license taxes, unemployment insurance taxes, individual income

taxes paid by owners of non-corporate (pass-through) businesses, and other state and local taxes

that are the statutory liability of business taxpayers (Ernst & Young, 2012, p.1).” This is a

broader range of taxes than what is included in the hypothetical firm studies above. The Ernst &

Young study does not take tax shifting to another state into account; however, except for the case

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

6

of severance taxes and tourism taxes, there is no reason to think that firms in one state can shift

taxes more than firms in another state. State and local taxes as a percentage of private gross state

product are presented in Graph 1. For all of the states, local taxes are a lower percentage than

state taxes. For Missouri, the state with the lowest taxes as a percentage of private gross state

product, the two taxes are nearly the same percentage.

GRAPH 1: STATE AND LOCAL BUSINESS TAXES AS A PERCENTAGE OF PRIVATE

GROSS STATE PRODUCT, 2011*

*Private gross state product is the total value of annual production of goods and services within the state by the

private sector (i.e. nongovernmental, business entities) (Ernst & Young, 2012, p. 10).

Source: Ernst & Young 2012, Table 4, p.11.

Taxes Per Capita and Per $1,000 of Personal Income

Researchers have also looked for easier ways to calculate tax comparisons, such as taxes per

capita, and taxes per $1,000 of personal income (or as a percentage of personal income). These

calculations include all taxes in the state, not just business taxes. These are used for several

reasons: 1) data on tax revenues, population and personal income are readily available by state;

2) all taxes at some point are paid by individuals (even the corporate income tax is passed to

individuals in the form of lower dividends and/or higher prices because taxes are a cost to the

firm); and 3) because all taxes are included, no assumptions are required to allocate how much of

a tax (such as the property tax) is paid by businesses versus individuals. While the effective tax

rate will differ from the previous calculations there is no a-priori reason to think that rankings

will be affected in one direction or another.

2.5%

3.2%

2.5%

2.2%

3.6%

3.1%

2.7%

2.5%

3.6%

1.9%

1.8%

2.4%

2.1%

1.5%

2.4%

2.0%

2.3%

0.9%

0.0% 1.0% 2.0% 3.0% 4.0% 5.0% 6.0%

Tennessee 2

Oklahoma 8

Nebraska 6

Missouri 1

Kentucky 8

Kansas 9

Iowa 4

Illinois 5

Arkansas 3

State Total as % of private GSP Local Total as % of private GSP

State Rank

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

7

TABLE 4: STATE AND LOCAL TAX REVENUE PER CAPITA AND AS A

PERCENTAGE OF PERSONAL INCOME*

State

Per Capita State & Local

Tax Revenue, 2009

State

Rank

State & Local Tax Revenue as a

Percentage of Personal Income,

2009

State

Rank

Arkansas

$3,262

4

10.2%

5

Illinois

$4,397

9

10.8%

9

Iowa

$3,717

6

10.6%

8

Kansas

$4,070

7

10.6%

8

Kentucky

$3,213

3

10.0%

4

Missouri

$3,210

2

8.9%

2

Nebraska

$4,092

8

10.5%

6

Oklahoma

$3,319

5

9.7%

3

Tennessee

$2,841

1

8.4%

1

*1 is the lowest rank and indicates the lowest tax level.

Source: O’Leary Morgan and Morgan (2012), p. 301 & 303.

Missouri has the 2

nd

lowest taxes on these two measures, with only Tennessee lower. As shown

in Graph 1 Missouri had the lowest taxes as a percentage of private state gross product. The data

presented in Graph 1 and Table 4 are consistent across most states; Kansas is among those in the

highest third of states on the measures in Graph 1 and Table 4. The ranking of Illinois, however,

ranges from highest in Table 4 to fifth in Graph 1.

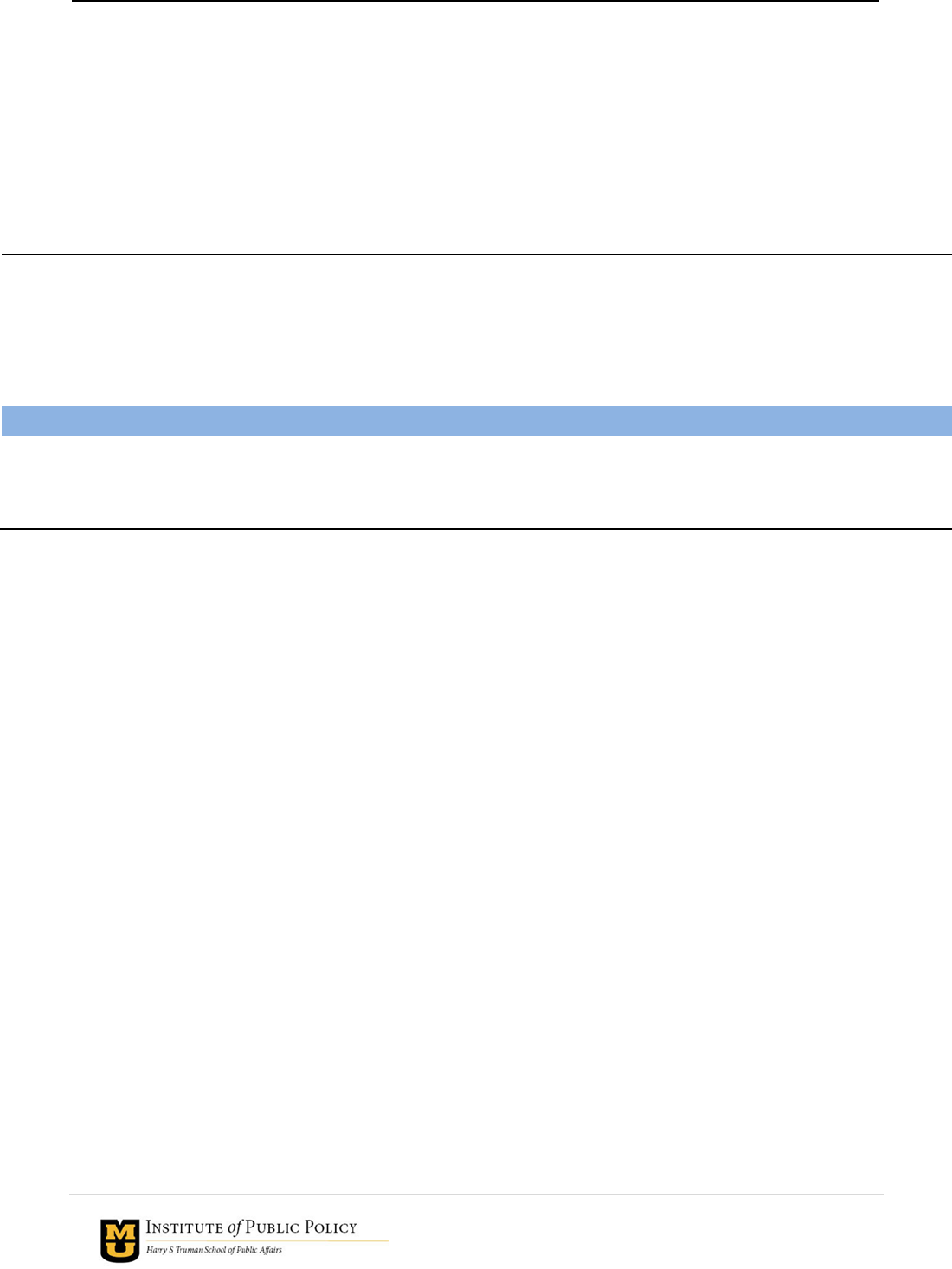

Discussion and Conclusion

Table 5 presents a summary of state rankings from the analysis above to demonstrate both the

variability and consistency of state tax data across these very different measures.

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

8

TABLE 5: SUMMARY OF STATE TAX RANKINGS ON HYPOTHETICAL FIRM

ANALYSES, PERCENTAGE OF PRIVATE GSP, REVENUE PER CAPITA AND AS

A PERCENTAGE OF PERSONAL INCOME *

State

Ernst &

Young

Hypothetical

Firm Rank

Tax

Foundation

Hypothetical

Mature Firm

Rank

Tax

Foundation

Hypothetical

New Firm

Rank

Ernst & Young

Business Taxes as

a Percentage of

Private GSP,

2011 Rank

State &

Local Tax

Revenue

Per Capita,

2009 Rank

State & Local

Tax Revenues as

a Percentage of

Personal Income,

2009 Rank

Arkansas

6

5

4

3

4

5

Illinois

1

8

5

5

9

9

Iowa

2

7

8

4

6

8

Kansas

9

9

9

9

7

8

Kentucky

3

3

3

8

3

4

Missouri

4

6

6

1

2

2

Nebraska

7

1

1

6

8

6

Oklahoma

5

2

2

8

5

3

Tennessee

8

4

7

2

1

1

*1 is the lowest rank and indicates the lowest tax level.

Source: Ernst & Young (2011) Table 2, p. 9; Tax Foundation (2012) Table 1, p. ix; O’Leary Morgan and Morgan

(2012), p. 301 & 303.

We find some consistency in the rankings across the states. In particular, Arkansas, Kentucky,

Missouri, and Tennessee typically are the states with lowest taxes. Conversely, Illinois, Iowa,

Kansas, and Nebraska generally are among the states with higher taxes. Oklahoma, however,

generally ranks close to the middle on most measures. Part of the variability is because each

measure makes different assumptions and these assumptions affect the results. A state’s tax

system can be portrayed in either a positive or negative light, depending upon which metric one

chooses to utilize. Thus, it is crucial to consider multiple methods for examining state tax

systems.

Note that in all measures, except those from the Tax Foundation study, Missouri ranks lower

than fifth (that is, among those with lowest taxes) while Kansas ranks ninth on four of the six

measures (and ranks seventh and eighth on the remaining two). These findings have important

implications given the recent tax cuts enacted in Kansas in hopes of spurring economic

development and the push by its neighbors, including Missouri, to follow suit. If low taxes lead

to economic development, then Missouri and several of its neighbors, with consistently low to

mid-range taxes should be experiencing substantially higher levels of economic development

than others in this comparison.

Proposals for tax cuts in Missouri must take into account the provisions of the Hancock

Amendment. This Amendment limits annual legislatively approved tax increases to $84 M in

FY 2013, without voter approval, making it quite difficult to increase taxes once they are cut. If

Missouri adopts significant tax cuts, it will have substantial difficulty raising taxes if the need

arises. In contrast, the same policy obstacles do not exist for Kansas, as it is not limited by

legislation like the Hancock Amendment.

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

9

But a wide range of costs factor into firms’ decisions, not just tax rates and taxes paid. In fact,

Ernst & Young (2012) suggest that non-tax cost differentials, such as labor, utility, and

transportation costs are generally “the most significant variable business costs” which

substantially influence firms’ investment location decisions. There is also evidence that firms

consider factors not directly related to either taxes or incentives when evaluating locations,

including infrastructure, availability of a quality work force, and quality of life issues (Karakaya

& Canel, 1998; Love & Crompton, 1999; Gabe & Bell, 2004).

Taxes are only one of the policy levers that states have at their disposal. The other side of the tax

coin is state expenditures, which influence firms’ costs, such as transportation, public safety and

education. In a review of the literature, Fisher (1997) finds that in general, public services,

government spending, and public capital—specifically transportation, public safety, and

education—have both a positive and statistically significant impact on economic development.

In addition several reviews of the literature that focus on both taxes and expenditures find that

any positive impact of a tax cut is less than the negative impact of the corresponding cut in

public spending (Bartik 1992 and 1994, Lynch 2004). Lynch (2004, p. 12) argues that

“businesses need to know that they can rely on high-quality, well-administered public services to

facilitate the conduct of their enterprises.”

In sum, this analysis demonstrates that no single metric or study can provide a comprehensive

understanding of a state’s tax system, given the substantial variability that can exist. However,

when multiple analyses reveal consistent results, it is possible to make preliminary conclusions.

As underscored above, Missouri consistently ranked among the lower half of its neighbor states

on a majority of the six measures of effective tax rates used in this analysis. In addition, there

are numerous other factors not directly related to taxes that can impact states attractiveness and

competiveness including expenditures for public services on which businesses rely (e.g.

transportation, public safety, and education).

References

Bartik, T. (1992). The Effects of State and Local Taxes on Economic Development: A Review of Recent

Research. Economic Development Quarterly, 102-110.

Bartik, T. (1994). Jobs, Productivity, and Local Economic Development: What Eceonomic Implications

does Economic Research Have for the Role of Government? National Tax Journal, 847-861.

Ernst & Young. (2011). Competitiveness of State and Local Business Taxes on New Investment: Ranking

States by Tax Burden on New Investment. Washington D.C.: Ernst & Young. Retrived from

http://www.cost.org/Page.aspx?id=69994

Ernst & Young. (2012). Total State and Local Business Taxes: State-by-State Estimates for Fiscal Year

2011. Washington DC: Ernst & Yong. Retrived from http://www.cost.org/Page.aspx?id=69654

Fisher, R. C. (1997). The Effects of State and Local Public Services on Economic Development. New

Engalnd Economic Review, 54-82.

Gabe, T. M., & Bell, K. P. (2004). Tradeoffs between Local Taxes and Government Spending as

Determinants of Business Location. Journal of Regonal Science, 21-41.

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

10

Karakaya, F., & Canel, C. (1998). Underlying Dimensions of Business Location Decisions. Industrial

Management and Data Systems, 321-329.

Love, L. L., & Crompton, J. L. (1999). The Role of Quality of Life in Business (Re)Location Decisions.

Journal of Business Research, 211–222.

Lynch, R. G. (2004). Rethinking Growth Strategies: How State and Local Taxes and Services Affect

Economic Development . Washington DC: Economic Policy Institute. Retrived from

http://www.epi.org/publication/books_rethinking_growth/

O'Leary Morgan, K., & Morgan, S. (2012). State Rankings 2012: A Statistical View of America. CQ Press

and SAGE Publications.

Peters, Mark. “Kansas Governor Signs Tax-Cut Bill: Drop in Income-Tax Rates, Backed by Tea Party

as Economic Stimulus, Drew Flak From Some in GOP.” The Wall Street Journal, US Edition.

May 22, 2012, 9:12 p.m. ET.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304791704577418641784902500.html

Tax Foundation . (2012). Location Matters: A Comparative Analysis of State Tax Costs on Business.

Washington DC: Tax Foudation. Retrived from

http://taxfoundation.org/sites/taxfoundation.org/files/docs/location%2520matters.pdf

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

11

APPENDIX A: HYPOTHETICAL FIRM ANALYSIS ASSUMPTIONS

Ernst & Young

Tax Foundation

The analysis is for C corporations, not pass

through entities.

The analysis is for C corporations, not pass

through entities.

For a 30-year investment beginning in 2009.

For a single year—2011.

Focused on mobile firms: headquarters, research

and development, office and career center, and

both durable and non-durable manufacturing.

Focused on mobile firms: corporate

headquarters, research and development center,

capital-intensive manufacturing, labor-intensive

manufacturing, call center, distribution center,

and retail store.

Taxes included: corporate income, franchise and

gross receipts taxes; sales and use taxes on

business purchases; and property taxes.

Taxes included: property taxes, corporate

income taxes, sales taxes, unemployment

insurance taxes, capital stock taxes, inventory

taxes, and gross receipt taxes.

Included sales taxes only on business purchases;

did not include retail sales taxes charged to

consumers.

Included sales taxes on business purchases and

retail sales taxes charged to consumers.

The property tax rate of the largest city in the

state is used. For Missouri it is St. Louis.

Uses two sizes of cities and each type of firm is

located only in the larger or smaller city. For

Missouri these are St. Louis and Joplin.

The local sales tax rate is the weighted average

by sales of local sales taxes.

The local sales tax rate is based on the location

of the hypothetical firm. For Missouri this is St.

Louis or Joplin.

Does not include the unemployment insurance

tax because the tax is firm specific.

Includes the unemployment insurance tax.

Calculated the effective tax rate over a 30-year

investment beginning in 2009 and phased in

changes that are written into current tax law

through 2014.

Calculated effective tax rates for a single year,

2011. Effective tax rates are converted to an

index—the percentage above or below the

national average tax rate for that type of firm.

The national average is set at 100.

Included tax credits available to most firms, but

did not include discretionary incentives. Taxes

specific to a particular industry—severance tax,

utility tax, etc. are not included as these types of

firms were not included as hypothetical firms.

Mature firms are not eligible for incentives.

Included discretionary incentives for new

firms—new job credits and new hire withholding

rebates, investment tax credits, R&D credits,

property tax abatements, exemptions for sales

taxes on equipment, depreciation of buildings

and personal property.

The analysis does not estimate tax shifting by the

firm to other business entities or consumers

except for the retail sales tax, which it assumes

consumers pay.

The analysis does not estimate tax shifting by the

firm to other business entities or consumers. It

assumes that firms do not shift the retail sales tax

to consumers.

Calculated a weighted overall tax rate for all

firms using the percentage of new investment in

each type of firm as the weight.

Calculated the overall tax rate for all firms by

using a simple average of the types of

hypothetical firms.

Source: Ernst & Young (2011); Tax Foundation (2012).

Comparing Taxes in Missouri and Surrounding States Report 07-2013

12

APPENDIX B: EFFECTIVE TAX RATE NATIONAL RANKINGS OF MISSOURI

AND NEIGHBORING STATES *

State

Ernst &

Young

National

Rank

Tax

Foundation

Mature Firm

National

Rank

Tax

Foundation

New Firm

National

Rank

State & Local

Tax Revenue

Per Capita,

2009 National

Rank

State & Local

Taxes as a

Percentage of

Personal Income,

2009 National

Rank

Ernst & Young

Business Taxes as a

Percentage of Private

GSP, 2011* National

Rank

Arkansas

36

30

8

13

23

16.5

Illinois

5

45

24

37

35

23.5

Iowa

14

40

41

28

31.5

21.5

Kansas

48

47

48

32

31.5

35.5

Kentucky

15

18

7

11

20

30.5

Missouri

22

36

26

10

5

9.0

Nebraska

41

9

1

33

28

26.0

Oklahoma

35

16

5

14

15

30.5

Tennessee

45

29

29

2

2

13.5

*1 is the lowest rank and indicates the lowest tax level.

Source: Ernst & Young (2011) Table 2, p. 9; Tax Foundation (2012) Table 1, p. ix; O’Leary Morgan and Morgan

(2012), p. 301 & 303; Ernst & Young (2012) Table 4, p.11 .