California State University, Monterey Bay California State University, Monterey Bay

Digital Commons @ CSUMB Digital Commons @ CSUMB

Capstone Projects and Master's Theses

Spring 2016

Impact of a Contingency Cell Phone Plan on Secondary Students’ Impact of a Contingency Cell Phone Plan on Secondary Students’

On-Task Behavior On-Task Behavior

Lindsay Hack

California State University, Monterey Bay

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Hack, Lindsay, "Impact of a Contingency Cell Phone Plan on Secondary Students’ On-Task Behavior"

(2016).

Capstone Projects and Master's Theses

. 564.

https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/564

This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital

Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB

review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information,

please contact [email protected].

Running head: CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON- TASK BEHAVIOR 1

ImpactofaContingencyCellPhonePlanonSecondaryStudents’on-task Behavior

Lindsay Hack

Action Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of

Arts in Education

California State University Monterey Bay

May 2016

©2016 by Lindsay Hack. All Rights Reserved

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 2

ImpactofaContingencyCellPhonePlanonSecondaryStudents’on-task Behavior

By: Lindsay Hack

APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE

__________________________________________________

Jaye Luke, Ph.D., Advisor, Master of Arts in Education

__________________________________________________

Kerrie Chitwood, Ph.D., Advisor and Coordinator, Master of Arts in Education

__________________________________________________

Kris Roney, Ph.D. Associate Vice President

Academic Programs and Dean of Undergraduate & Graduate Studies

Digitally signed by Kris Roney, Ph.D.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 3

Table of Contents

ImpactofaContingencyCellPhonePlanonSecondaryStudents’on-task Behavior ................... 5

Literature Review ........................................................................................................................ 5

On-task Behavior ..................................................................................................................... 5

Behavioral Interventions .......................................................................................................... 6

Research Question ................................................................................................................. 14

Methods ..................................................................................................................................... 14

Setting .................................................................................................................................... 14

Participants ............................................................................................................................ 15

Materials/Instruments ............................................................................................................ 16

Measurement ......................................................................................................................... 16

Design and Procedures .......................................................................................................... 16

Interobserver Agreement ....................................................................................................... 17

Procedural Fidelity ................................................................................................................ 18

Social Validity ....................................................................................................................... 18

Results ....................................................................................................................................... 19

Discussion ................................................................................................................................. 21

References ................................................................................................................................. 26

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 4

Abstract

Use of technology as a tool for reinforcement to increase on-task behavior is imminent given the

role of technology in society. This study utilizes the implementation of a contingency cell phone

plan designed to increase on-task behavior. An ABAB design was employed with at-risk,

secondary students receiving special education services in a continuation high school. Three

male students, ages 16-18, with a diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

were selected due to difficulty with on-task behavior. Participants were granted access to their

cell phone after demonstrating 5 minutes of on-task behavior. On-task behavior was defined as

any behavior that did not include looking at their cell phone. The results indicated a significant

increase in on-task behavior when using a contingency cell phone plan as a tool for

reinforcement. Given the scant research on technology as a tool for reinforcement, this study

and future studies will provide meaningful data into use of this strategy in the educational

setting.

Key words: on-task, secondary, reinforcement, technology

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 5

Impact of a Contingency Cell Phone Plan on SecondaryStudents’on-task Behavior

Literature Review

On-task Behavior

On-task behavior is a construct. That is, researchers have defined it differently depending

on their purpose or task (Galton, Hargraves, Comber, Wall & Pell, 1999; Gill & Remedios, 2012;

VandenBerg, 2001). For example, VandenBerg (2001) used on-task behavior to represent

engagement with the learning materials. Engagement indicated that if students were interacting

with the learning materials (e.g., book, graphs, etc.), then they were considered on-task. On-task

behavior could include using the materials appropriately along with engaging in task-related

conversations (Gill & Remedios, 2012). Furthermore, Galton and colleagues (1999), included

requiring the student to be fully involved with the assignment to be counted as on-task behavior.

These varying definitions allow for a flexibility in research and for interested individuals to

clearly identify which academic behaviors they are interested in measuring; as it is clear that on-

task behaviors can range from interaction with materials to correct responses on an assignment

within a given time.

This range of behaviors clarifies the importance of the on-task construct. The scope of

on-task behavior is often correlated with academic success (Heering & Wilder, 2006). For

example, on-taskbehaviorincreasesastudent’sgradepointaverage(GPA),decreasingthe

student’sriskofschooldropout.Giventhatmanystudents,whodonotsuccessfullycomplete

high school with a diploma remain unemployed, their chances of incarceration and dependency

on social services escalate dramatically (Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, 2008). For at-risk

students, improving their GPA and decreasing their risk for dropout helps prepare them to be

successful in school as well as in their professional life. Therefore, it is important to help

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 6

students develop the skills to be on-task in an academic environment (Wills & Mason, 2014).

Teaching on-task behaviors to students is a well-researched topic and a myriad of interventions

to improve on-task behavior have been successful for various student populations.

Behavioral Interventions

Many studies have identified interventions that increase on-task behavior for students in

the general education and special education settings. Research has shown that interventions have

been proven effective for students in whole class settings as well as for individual needs (Allday

& Pakurar, 2007; Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, 2008; Bedesem & Dierker, 2014; Bonus &

Riordan, 1998; Calderhead, Filter, & Albin, 2006; DuPaul & Weyandt, 2006; Galton, Hargraves,

Comber, Wall & Pell, 1999; Heering & Wilder, 2006; Moore, Anderson, Glassenbury, Lang &

Didden, 2013; Panahon & Martens, 2012; Skinner, 2002; VandenBerg, 2001; Wills & Mason,

2014). Whole-class interventions tend to focus on increasing attentive, engaged behavior

amongst all students while individualized interventions target a specific behavior for an

individual student.

Teachers utilize whole-class interventions for on-task behavior to create positive learning

environments. Allday and Pakurar (2007) examined the effect of teacher greeting on students

on-task behavior. Using antecedent manipulation, a secondary classroom teacher greeted

students as they entered the general education classroom. In addition to the greeting, a

personalized comment was made. The researchers found a mean increase of 27% of on-task

behavior during the intervention phase, suggesting that students are more likely to demonstrate

on-task behavior when presented with a positive antecedent event (Allday & Pakurar, 2007). For

many students a warm, welcoming teacher provides students the confidence and inspiration to

meet academic expectations.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 7

Another whole-class intervention often used within the classroom is seating

arrangements. Teachers use seating to diffuse social tension, encourage academic support

among peers and foster productive learning environments. For example, Bonus and Riordan

(1998) investigated the use of specific seating arrangements as an intervention to increase on-

task behavior. Findings from this study demonstrated that dependent upon the type or format of

instruction, whole class seating arrangements were influential in increasing on-task behaviors

(Bonus & Riordan, 1998). Teachers can implement the use of varying seating arrangements;

however, this strategy does not ensure on-task behavior.

Even within a perfect classroom setting, typically atleastonestudent’sbehavior disrupts

the learning environment. To address these classroom behavior issues teachers often use

contingency-based systems to redirect or address target behaviors. Using independent,

interdependent or dependent group contingencies, teachers can provide students with the same

reinforcer dependent upon the contingency in place. Independent group contingencies address

one target behavior for all students, where the student earns the reinforcement based upon his or

her behavior. Interdependent group contingency systems allow a group of students to earn the

reinforcer given the group behavior. Dependent group contingencies provide reinforcement to

the whole group dependent upon on or a few students meeting the target behavior. Heering and

Wilder’s (2006) research with elementary students on increasing on-task behavior through

dependent group contingency systems indicated extremely positive results. That is, on-task

behavior rose from a mean of 36% to 83% in a third grade classroom and from 50% to 85% in a

fourth grade classroom. Follow-up levels conducted during the study continued to show that

high levels of on-task behavior were maintained with a mean of over 90%. This research points

to the importance of group contingency systems and their effectiveness within the classroom.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 8

While whole group or classroom based interventions are extremely beneficial to students,

individualized interventions must be implemented for students who are identified at-risk or have

severe behavior needs.

For students with more challenging or prominent behaviors, identifying the function of

the behavior is imperative for choosing the appropriate intervention. For secondary students, the

function of the behavior is often to avoid tasks or a paucity of executive functioning skills.

Many students who engage in off-task behavior due to learning challenges have found success in

interspersed requests or stimulus variation of instructional tasks (Calderhead, Filter, & Albin,

2006). For example, a student with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) who

loathes division may be more successful in completing the assignment when a few addition or

subtraction problems are mixed also included in the assignment. Perhaps the student is more

inclined to finish the task because they are less frustrated or they may find the easier, preferred

item fun and rewarding.

Skinner (2002) proposed that interspersing preferred tasks with more challenging tasks

increases the rate of reinforcement for task completion. Completion of the easier, or preferred

task, becomes a conditioned reinforcer, thereby increasing on-task behavior (Skinner, 2002).

Along with interspersing modified tasks within an assignment, many teachers find allowing

students with behavior challenges to choose an assigned academic activity is an effective

intervention.

Choice-making interventions provide students with teacher approved task options within

an area of study. For example, a student who finds writing aversive may choose to make a

picture collage instead. The student avoids the act of writing, but illustrates mastery of the

concepts in a different way. Students who are allowed choice making within their classroom

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 9

have been shown to have increased rates of on-task behavior (DuPaul & Weyandt, 2006). In

addition to making choices, modifying assignments to increase accessibility has also been shown

to be effective. Modification may include a reduction of assigned tasks, creating sub-units, or

providing a brief break after task completion. Many students struggle with both academic needs

and, or executive functioning skills. For these students, self-management strategies are vital to

increasing on-task behavior.

Self-management strategies have been proven very effective to increase on-task behavior

for secondary students (Moore, Anderson, Glassenbury, Lang & Didden, 2013). Strategies for

self-managementinclude“self-monitoring, self-recording, self-evaluation, goal setting and self-

reinforcement”(Mooreetal.,2013,p.302).Teachingstudentstheseskillsearlycanpromote

educational success as well as generalizing to future employment. Furthermore, Wills and Mason

(2014) describe self-monitoring as a multi-step process in which students observe and record the

presence of the target behavior. Students may use visual calendars or charts to regulate and

reinforce on-task behavior. For example, a high school student with ADHD, may record the

number of paragraphs he read every five minutes to determine whether he remained on-task

during the class period. These types of visual strategies often aide students with their self-

management skills.

In addition to visual strategies, tactile or audio prompts are often used in self-

management interventions to cue the student’sbehavior.Mooreandcolleagues (2013) studied

the use of a tactile prompt for self-management of general education secondary students. In this

study, the use of an electronic beeper that vibrates re-directed students to remain on-task. The

mean increased on average by 39.1% during the intervention phase suggesting the use of a tactile

prompt to be very effective for increasing on-task behavior (Moore et al., 2013). Use of

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 10

electronics or technology in self-management has increased greatly over the past decade with the

surge of classroom access to tablets, small computers or handheld devices (Wills & Mason,

2014). For secondary students where assimilating with peers is essential, the use of technology

as an intervention is an appropriate tool.

Furthermore, technology as a potential intervention was investigated by Wills and Mason

(2014) using an android application that allows students to self-evaluate through text cues and

response. Both participants demonstrated an increase of over 40% of on-task behavior with the

use of the application, indicating an extremely effective intervention for these students (Wills &

Mason, 2014). In addition, the use of a cell phone as a self-monitoring tool has been determined

to increase on-task from 44% to 99% (Bedesem and Dierker, 2014). Researchers attributed this,

at least partially, to the level of acceptance of cell phones amongst students. Providing students

with a strategy that facilitates autonomy in self-regulation of their on-task behavior can be a

powerful experience (Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, 2008). Modifying academics,

providing choice activities and implementing self-management strategies are fundamental

interventions for increasing on-task behavior. In addition to the aforementioned interventions,

consequent based systems play in important role in behavior interventions.

Contingency based consequence systems, such as providing a reinforcer following a

target behavior, have a long history of empirically based evidence supporting practice in the

classroom (DuPaul & Weyandt, 2006). For example, if a student demonstrates on-task behavior

by engaging with the lesson material or discussing the academic task with a peer the student

receives a ticket. The ticket acts as a reinforcement, or acknowledgement of the student

displaying appropriate on-task behavior. Given the student understands the value of the ticket,

she is more likely to continue to engage in on-task behavior. For at-risk secondary students and

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 11

those in a special education program, contingency based interventions increase motivation along

with decreasing the target behaviors (Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, 2008). To have an

effective contingency based, consequent strategy identifying effective reinforcement is

imperative.

Research has shown that an intervention is only as successful as the reinforcement it

provides to the student (Fielder, 2007). For many educators this is a difficult concept to

understand.Herrnstein’s(1961,1970)matchinglawexplainstheconstructofreinforcementas

the amount of time a student engages in a behavior as a function relative to the rate the behavior

is reinforced. Using this construct, educators can increase the rate of appropriate behavior by

supplying an adequate quantity of positive reinforcement. Fielder (2007) explains that positive

reinforcement is the presentation of a stimulus which increases the frequency of the target

behavior. When selecting the type of reinforcement, one must also consider the schedule of

reinforcement and the delivery system.

Interval schedules of positive reinforcement have been used to control on-task behavior

with affirmative results (Skinner, 2002). Interval schedules of reinforcement can be provided

through fixed or variable intervals. For example, a student who has challenges remaining in their

seat may receive a reinforcer after every five minutes, which is a fixed interval schedule, or at

randomly selected times throughout the session, a variable interval schedule. Along with a time

schedule, interventions are constructed with specific delivery systems. The reinforcement can be

delivered through non-contingent or contingent based systems. Non-contingent systems deliver

stimuli at a fixed time interval regardless of student behavior. For example, every 20 seconds the

teacher gives the student a ticket whether or not the student is demonstrating the target behavior.

Panahon and Martens (2012) found that contingent based systems, or delivery of stimuli

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 12

contingent upon student behavior, are a more effective delivery method compared to non-

contingent systems. Contingent systems require the student to meet an objective prior to

receiving the reinforcement. For example, if the target behavior was task completion, once the

discrete task was completed the student is reinforced through use of a preferred item for a fixed

time (Skinner, 2002). While the schedules and system of reinforcement are the foundation of an

intervention, the most essential piece is selecting the appropriate reinforcer for the individual

student or group of students. For the educator it is critical to recognize the importance of

extrinsic motivation and utilize student choice in stimuli, which will establish student

engagement in the task, increasing the magnitude of reinforcement (Appleton, Christenson, &

Furlong, 2008; Hoffmann, 2014). Using contingent based systems of reinforcement with highly

preferred items as the reinforcer has been shown to be extremely effective in increasing on-task

behavior (Skinner, 2002).

Highly preferred reinforcers for secondary students can vary greatly from those of

younger children. Providing specific, valued, reinforcement becomes paramount to the success

of the intervention as the individuality of favored items increases, with maturation of students

(Fielder, 2007). Given the variation of preferred reinforcers among individuals and ages,

determining choice items for the student is paramount. Using stimulus preference assessments

canbeusefulinidentifyinghighlypreferredreinforcersforsecondarystudents.Fielder’s(2007)

research maintained that teacher and student preference varied in each stimulus preference

assessment, concluding that selecting the appropriate reinforcer is not always obvious and

requires student input. Given that the most successful interventions are easy and quick to

implement, finding a highly preferred reinforcer that falls under those same conditions and is

socially acceptable is fundamental. For secondary students, using a reinforcer that does not stand

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 13

out is key. Using technology as a reinforcer for more mature students enables them to remain

inclusive with their peers, while accessing a highly preferred item.

In the past decade, high-tech stimuli have become a highly preferred reinforcer for

students (Hoffmann, 2014). High-tech devices, defined as using batteries or electricity, with

sophisticated computer components, consist of items such as personal gaming devices, laptops,

tablets, cellphones, etc. (Hoffmann, 2014). High-tech devices, specifically cell phones, have

become easily accessible in the United States, providing opportunity for use as a reinforcer for

secondary students. A recent study by Pew Research Center, states 88% of teens in the United

States have or have access to a cell phone and it is their preferred form of communication

(Lenhart, 2015). In her research on high tech stimuli as a reinforcer, Hoffman (2014) attributed

the production of response-dependent and response-independent changes in high-tech devices

such as cell phones, as the rationale behind the high rate of reinforcement provided by

technology for students.

Furthering the discussion of cell phones as a reinforcer, Wei and Wang (2010) used the

gratification model to provide rationale for cell phone use in the classroom stating that cell

phonesprovidedreinforcementintheconstructsof“pleasure,relaxation, escape, inclusion and

affection”(2010,p.481). While there is scant research specifically on the use of cell phones as a

reinforcer in the classroom, as students are innately drawn to the use of technology, exploration

of this area is imminent. Given that 75% of students’ report carrying their cell phones to class

(Froese, et al., 2012) and over 90% of students reported sending text messages during class (Ali,

Papakie, & McDevitt, 2012), it would be reasonable to say, further study in this area is essential.

Use of a cell phone as a reinforcer for at-risk, secondary students in a special education program

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 14

increases the sustainability of the intervention, by being a highly preferred item, easily accessible

and socially acceptable amongst peers (Wills & Mason, 2014).

This study will examine how the implementation of a cell phone use contingency plan

will affect the rate of on-task behavior of at-risk, secondary students, in a special education

program. Currently, there is a plethora of research around interventions for general education

and special education of various ages, however there is little research specifically looking at

interventions to increase on-task behavior for secondary students using technology as the

reinforcer, not a tool for the intervention. The data gathered throughout this study will be highly

beneficial to administrators, teachers and students in the secondary setting by providing a

strategy to use cell phones to increase student motivation.

Research Question

How does the implementation of a cell phone use contingency plan affect the rate of on-

task behavior of at-risk, secondary students, in a special education program?

Methods

Setting

The study took place throughout 19 sessions lasting in a guided studies classroom that

lasts 50 minutes in a continuation high school in Santa Clara County. The high school serves

students who have not previously been successful in a comprehensive high school setting. The

school capacity is approximately 180 students, ages 16-19, with 12% of its population receiving

Special Education services (Bowen, 2015). The high school is in a suburban community, with

30% of its 52,000 inhabitants under the age of 18. Approximately 57% of its population

identifies itself as Hispanic or Latino in origin with 15.5% of the population reported as below

poverty level (United States Census, 2014).

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 15

The school district board policy states cell phone use is prohibited during instructional

minutes, including passing periods. Students may use their cell phones during brunch and lunch.

If a student uses their cell phones during instructional time, they are instructed to put the device

away. If a student refuses or uses the phone again, parent contact will be made and additional

consequences may ensue. If the behavior becomes habitual, office discipline referrals are given

and severe consequences may be warranted.

Participants

Three males ages 16-18, with a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,

combined type, participated in this study. Each participant was assigned a pseudonym to ensure

confidentiality and anonymity. Participants received special education services through

mild/moderate specialized academic instruction. Participants were selected based on teacher

nomination due to chronic use of their cell phone during class time. Each participant had

received a minimum of three office discipline referrals due to cell phone use. All three students

attended a full five-and-a-half-hour day at school, with one period of special education support

through their Guided Studies class.

Alfonso was 17 years old and has received Special Education services since 2011. Since

attending the current school, Alfonso had earned 12 credits and is not on track for graduation.

Austin was 18 years old and has received special education services since 2006. He is on

track for graduation in June of 2016.

Jacob was 16 years old and has received Special Education services since 2014. Jacob

has earned 83 credits and is on track to return to his comprehensive high school for his senior

year.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 16

Materials/Instruments

The materials used for this study were the participant's cell phone, data collection form,

timer, teacher survey, and a participant self-assessment. The cell phone is the property of and

provided by the participant. Thedatacollectionformincludedtheparticipant’spseudoname,

date of observation, five rows indicating the start and end time of the observation period and five

columns representing each day of the week. The researcher used an online timer with an

automated alert set for five-minute intervals.

Measurement

Direct observation of the on-task behavior was observed at least four days a week using a

five-minute partial interval recording system (Todd, Campbell, Meyer, & Horner, 2008).

Observations were consistent across class periods. The researcher used an online timer to time

the five-minute intervals. The first interval started approximately five minutes after the class

period began. There were five intervals per class session. On-task behavior was defined as the

participant not looking at or using their cell phone. Researchers noted their observations and

marked thenumber“0” if a participant used their cell phone at any point during the interval. If

the participant did not use or look at their phone, the researcher noted the observation with the

number“1”toindicateon-task behavior. Researchers received training in identifying on-task

behavior, completion of the data collection sheet, and use of the online timer.

Design and Procedures

To investigate the impact of a contingency cell phone plan as a reinforcer for on-task

student behavior, the research team developed a study using an ABAB design. Throughout all

phases of the study, participants were instructed to place their cell phone in the top left hand

corner of their desk or table. During baseline, participants were observed in five-minute

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 17

intervals during their classroom environment. During each interval, the researcher documented

cell phone use by the participant. The school policy of no cell phones allowed during class was

enforced.

During the intervention phases of the study, a contingency use plan was in place.

Participants were instructed that if they demonstrated on-task behavior for five minutes, defined

for this study as not looking at or touching their cell phone, they could use their cell phone for a

two-minute period at the conclusion of each five-minute interval. Participants who did not

demonstrate on-task behavior during the five-minute interval did not have access to their cell

phone during the two-minute interval and it remained at the top left corner of their desk. Each

series of intervals, the five-minute and two minute, acted independently of one another. For

example, a participant that did not earn the two-minute cell phone time after the first interval had

the opportunity to earn the second segment of cell phone time if they demonstrated on-task

behavior during the second five-minute interval. Participants were moved from baseline to

intervention after three stable data points. Participants returned to baseline after an increase of

25% or more of on-task behavior. Participants entered the second intervention phase after at

least three stable data points.

Interobserver Agreement

During the data collection process, a second researcher collected data for 25% of the

sessions. The second researcher was trained on how on-task behavior was defined for this study,

how to complete the data collection sheet and use of the online timer. The second researcher

collected data independently of the other researcher. Interobserver agreement was calculated by

dividing the total number of agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 18

and multiplied by 100%. Alfonso’smeanIOAwas94%. Austin’sIOArecordedon-task

behavior with a rate of 95% accuracy. Jacob had a mean IOA of 95% as well.

Procedural Fidelity

For 25% of sessions, an independent observer checked to see that the primary researcher

consistently implemented the cell-phone contingency. The second researcher determined

procedural fidelity by dividing the total number of correctly implementations by the number of

opportunities to implement the procedure and multiplied by 100 to determine percentage. The

contingency intervention was implemented correctly with 100% accuracy.

Social Validity

Social validity results were measured through teacher and student surveys. Social validity

was addressed by 12 teachers through the completion of a three-question survey prior to

participants entering baseline. The three questions were:

1. Are cell phones a distraction in your classroom?

YES NO

2. Is the current school policy of banned cell phones during instructional time effective?

YES NO

3. Would appropriate cell phone use strategies be beneficial in your classroom?

YES NO

Overall, teachers agreed that cell phones were a distraction in the classroom. Of the 12

teachers surveyed, 95% of them answered yes to the survey question of “Are cell phones a

distractioninyourclassroom?”Alloftheteachersconcurredthatcurrentpoliciesof banning

cell phone use during instructional time was ineffective. When asked if appropriate cell phone

usestrategiesbebeneficialintheclassroom,100%oftheteacherssurveyedsaid“yes.”

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 19

Participants addressed social validity through self-assessment surveys answered prior to

entering the initial baseline and after the final intervention. Participants were instructed on the

terms used in the questions and provided with an opportunity to ask questions about the self-

assessment survey. The three questions were:

1. Does use of your cell phone distract you during class?

YES NO

2. Do you accomplish more when your cell phone is not being used?

YES NO

3. Doesthepossibilityofusingyourcellphoneafteryou’vecompletedwork,makeyou

want to work harder?

YES NO

Participant surveys came back with mixed results. During baseline, when asked if the use of

theircellphonedistractthemduringclasstwooutofthreeparticipantsaid“no.”When

answering whether they accomplished more when their cell phones were not being used again,

allparticipantsresponded“no.”Forthefinalquestionof“Doesthepossibilityofusingyourcell

phoneafteryou’vecompletedworkmakeyouwanttoworkharder,”twoparticipantsmarked

“yes”andoneanswered“no”tothisquestion.Postintervention phase student surveys were all

returnedwithparticipantsanswering“yes”toallquestions.

Results

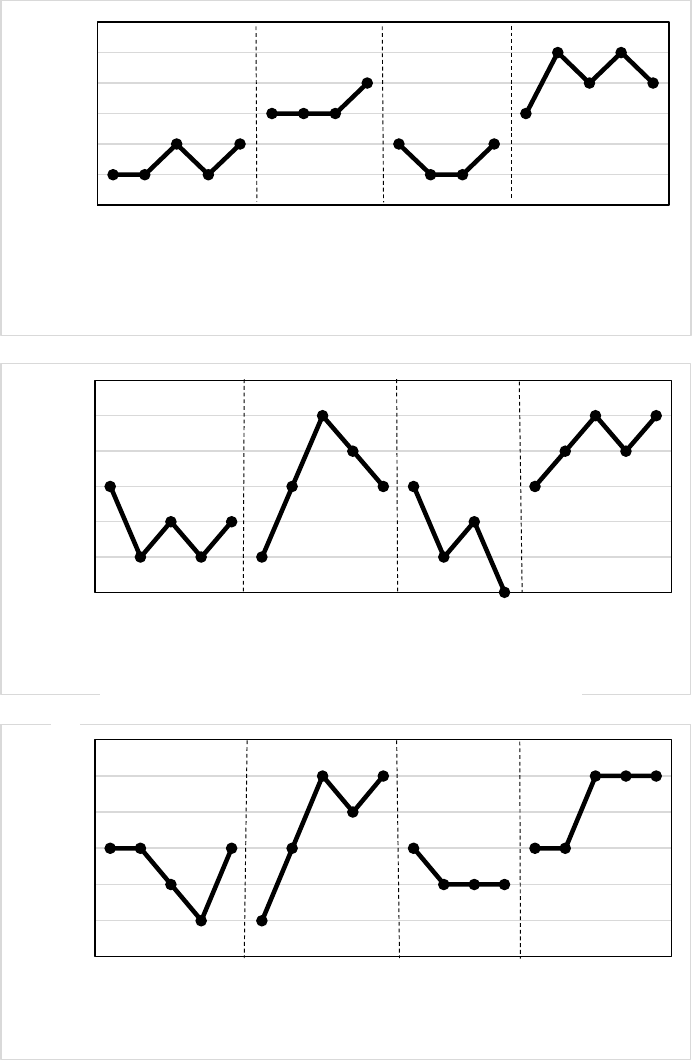

The impact of a cell phone contingency plan on on-task behavior is depicted in Figures 1,

2 and 3. The y-axisistheparticipants’percentageofon-task behavior. Sessions are displayed

on the x-axis.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 20

Figure 1 displays the results from Alfonso.Alfonso’smeanofon-task behavior during

Baseline 1 was 28% (range 20-40%). During Intervention 1 his average of on-task behavior

increased to 65% (range 60-80%). DuringBaseline2,Alfonso’son-task behavior decreased to a

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

Percentage of on-task behavior

Sessions

Series1 Series2 Series3 Series4

Figure 1. Alfonso’son-task behavior with and without the implementation of a cell-phone

contingency plan.

Baseline 1

Intervention 1

Intervention 2

Baseline 2

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Percentage of time on-task

Sessions

Series1 Series2 Series3 Series4

Intervention 1

Baseline 2

Intervention 2

Figure 2. Austin’son-task behavior with and without the implementation of a cell-phone

contingency plan.

Baseline 1

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Percentage of time on-task

Sessions

Series1 Series2 Series3 Series4

Baseline 1

Intervention 1 Baseline 2 Intervention 2

Figure 3. Jacob’son-task behavior with and without the implementation of a cell-phone

contingency plan.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 21

mean of 30% (range 20-40%). At the end of Intervention 2, Alfonso’son-task behavior rose to

an average of 84% (range 60-100) of time on-task.

Austin’smeanofon-task behavior during Baseline 1 was 36% (range 20-60%). During

Intervention 1 his average of on-task behavior increased to 64% (range 20-100%) (see Figure 2).

During Baseline2,Austin’son-task behavior decreased to a mean of 30% (range 0-60%). At the

end of Intervention 2,Austin’son-task behavior rose to an average of 84% (range 60-100) of

time on-task.

Figure 3 displays the results from Jacob. Jacob’smeanon-task behavior during Baseline

1 was 48% (range 20-60%). During Intervention 1 his average of on-task behavior increased to

72% (range 20-100%). During Baseline 2, Jacob’son-task behavior decreased to a mean of 45%

(range 40-60%). At the end of Intervention 2, Jacob’son-task behavior rose to an average of

84% (range 60-100) of time on-task.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that a contingency use cell phone plan is beneficial for

increasing on on-task behavior for secondary students in a special education program.

Throughout the study participants increased their on-task behavior by 26% to 56% from the

initial baseline to the final intervention phase. These results are comparable to previous studies

on on-task behavior using contingency based systems (Heering & Wilder, 2006). All

participants demonstrated significant improvement of their on-task behavior with the

implementation of the contingency use cell phone plan.

The first participant’sdatademonstrateafunctionalrelationwithnooverlappingdata

points, Alfonso displayed a more stable trend line which may be explained by his tendency to be

less emotional or impulsive than the other participants. Alfonso has shown to be more

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 22

intrinsically motivated, completing tasks and demonstrating self-advocacy, over time in

comparison to the other two participants. Given these personality traits, his trend line could be

attributed to his level of motivation and demonstration of stronger executive functioning skills.

While Alfonso appears to have the least amount of drastic movement amongst data points

compared to the other participants, he displayed the greatest gain in time on-task change from

baseline to intervention over the course of observation has the out of the three participants. This

was an interesting find for the researchers and potentially points to the impact emotional

regulation has on intervention results.

TheresearchersattributedmuchofAustin’sdatatohishighlyemotionalstate in which he

typically displays impulsive behavior with significant mood changes. Both Austin and Jacob had

60% of overlapping data points. When including the overlapping data points for Austin and

Jacob, their percentage increases to 90% leading the researcher to conclude the intervention was

highly effective for these participants as well.

While Jacob also demonstrates high rates of impulsivity, he tends to be less emotionally

oriented than Austin. However, Jacob required more“buy-in”whenitcomestoreinforcement

stimulus then either Alfonso or Austin which was apparent in his results.

However, even with fluctuating emotional needs, given the high rate of reinforcement a

cell phone provides, both Austin and Jacob made significant improvement in their rate of on-task

behavior. The value of a cell phone as a reinforcement tool can be seen as conclusive given all

three participants answered positively to this effect in the post intervention student survey. This

was verycleartoseeinJacob’sdatapointsinthefinalsessionsofeachinterventionphaseonce

he decided the contingency of work production was worth the payoff of cell-phone time.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 23

Each participant was able to move from baseline to intervention at the same time for each

phase as this was not the expectation. These three participants have a history of truancy;

therefore, the researchers expected absences to impede the transition between each phase.

However, during the research period, the participants were present for each day of school with

the exception of Alfonso who missed one day. Additionally, the researchers found it interesting

that each participant had a mean of 84% of on-task behavior in the final phase of Intervention.

There is no explanation for this consistency, however it is interesting to note. The survey data

provided the participants post intervention was a significant demonstration in how the

participants were able to identify both the detriment of cell phones as distractors, but also the

value of use of cell phones as reinforcer for task completion. Their consensus regarding cell

phones as avaluabletoolasareinforcercoincideswithHoffman(2014)andLenhart’s(2010)

research on secondary students and their adoration of technology.

Contingency based consequent intervention systems are extremely effective (DuPaul &

Weyandt, 2006) and identifying the appropriate reinforcer for the student/s ensures success of the

intervention (Fielder, 2007). In this current study the contingency based consequent system of

cell phone use post work completion proved successful. Given the cell phone is likely the most

highly preferred item of a secondary student at this time, the rate of reinforcement was

significant (Hoffmann, 2014). All three participants indicated that knowing they would have the

opportunity to access their cell phone after work competition was extremely motivating. Thus

student on-task behavior increased by utilizing the cell phone as a tool for reinforcement which

is an easily applicable strategy in the classroom.

The results of this study are an important contribution to current research and practice.

The use of cell-phones in secondary general education and special education classrooms as a

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 24

means of reinforcement could significantly impact school climate addressing student, teacher and

administrative needs by providing an effective, practical, and socially acceptable intervention

strategy.

As students become accustomed to cell phones as a tool, they will have the ability to

utilize cell phones as a tool for implementing free choice activities, for tactile prompting and

eventually for self-management and increasing executive functioning skills. Appropriate cell

phone use strategies could have a significant impact on increasing on-task behavior for

secondary students across settings. As we know from current literature, higher rates of on-task

behavior and student engagement has a positive impact on graduation rates, post-secondary

options and an increased likelihood of becoming a successful member of society (Appleton,

Christenson, & Furlong, 2008).

All teachers reported that the current policies regarding cell phones were ineffective and

95% of teachers agreed that cell phones were a distraction in their classrooms. Therefore, the

use of a contingency cell phone plan provides general education teachers a reinforcement that

would increase appropriate behaviors for the general education students as well as their students

participating in special education programs. Additionally, teachers and administrators would

have the advantage of providing cell-phone time for expected behavior versus the more common

strategy of removing cell phone use as a punishment. Policy changes allowing use of cell phones

as tools for reinforcement would allow administrators and teachers to implement effective

interventions for all students in the classroom.

Although the data showed positive results, the researchers found limitations with the

study and suggest alterations for future implementation. For future research it is suggested that

increasing the sample size and implementing the intervention across settings would be useful.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 25

For example, conducting the study in a general education classroom with 30 students including

those receiving special education services, could demonstrate the feasibility of the intervention

for all students and teachers. In this current study, researchers found the placement of the cell

phone to be a distraction to the participants as they could see and in some instances hear their

cell phone which impeded on-task behavior. The researchers suggest that participants place their

cell phones in a back pack or in a separate location in the room instead of on their desk in future

studies. The researchers also concurred, while it is important for the students to come in contact

with the reinforcer, the time allotment was too short for the age of the participants. Without the

appropriate length of time for reinforcement, the reinforcer may lose its value (Hoffman 2014).

It is suggested that the time on-task be increased to 15 minutes and the reinforcement period

increased to five minutes. It is reasonable to assume that with such a short time limit,

participants were unable to accomplish as much as they would have with a longer time allotment

for both task completion and the reinforcement period. With these alterations, the researchers

are certain utilizing cell phones as a tool for reinforcement would have a great impact to the

greater population.

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 26

References

Allday, R. A., & Pakurar, K. (2007). Effects of teacher greetings on student on-task behavior.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40, 317-320. doi:10.1901/jaba.2007.86-06

Ali, A., Papakie, M., & McDevitt, T. (2012). Dealing with the distractions of cell phone

misuse/use in the classroom-a case example. Competition Forum, 10, 220-230.

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school:

Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the

Schools, 45, 369-386. doi:10.1002/pits.20303

Bedesem, P., & Dieker, L. (2014). Self-monitoring with a twist: Using cell phones to cellf-

monitor on-task behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 16, 246-254. doi:

10.1177/1098300713492857

Bonus, M., & Riordan, L. (1998). Increasing Student On-Task Behavior through the Use of

Specific Seating Arrangements (Master’sthesis). Retrieved from Eric. (Order No.

422129)

Bowen, J. (2015, October). Single plan for student achievement. PowerPoint presented at the

meeting of Gilroy Unified School Board, Gilroy, CA.

Calderhead, W., Filter, K., & Albin, R. (2006). An investigation of incremental effects of

interspersing math items on task-related behavior. Journal of Behavioral Education, 15,

51-65. doi:10.1007/s10864-005-9000-8

DuPaul, G. J., & Weyandt, L. L. (2006). Schoolbased intervention for children with attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder: Effects on academic, social, and behavioural functioning.

International Journal of Disability, Development & Education, 53, 161-176.

doi:10.1080/10349120600716141

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 27

Fielder, C. E. (2007). Stimulus preference assessment in secondary general education: Using

reinforcement to increase on-task behavior (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. (Order No. 3293010).

Froese, A., Carpenter, C., Inman, D., Schooley, J., Barnes, R., Brecht, P. Chacon, J.

(2012). Effects of classroom cell phone use on expected and actual learning. College

Student Journal, 46, 323-332.

Galton, M., Hargreaves, L., Comber, C., Wall, D., & Pell, A. (1999). Inside the primary

classroom: 20 years on. London: Routledge.

Gill, P., & Remedios, R. (2013). How should researchers in education operationalise on-task

behaviours?. Cambridge Journal of Education, 43, 199-222. doi:

10.1080/0305764X.2013.767878

Heering, P. W., & Wilder, D. A. (2006). The use of dependent group contingencies to increase

on-task behavior in two general education classrooms. Education & Treatment of

Children, 29, 459-468.

Herrnstein, R. J. (1961). Relative and absolute strength of response as a function of frequency of

reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 4, 267–272.

doi: 10.1901/jeab.1961.4-267

Herrnstein, R. J. (1970). On the Law of Effect. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of

Behavior, 13, 243-266. Doi: 10.1901/jeab.1970.13-243

Hoffmann, A. N. (2014). The effects of high-tech stimuli and duration of access on reinforcer

preference and efficacy (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations &

Theses. (Order No. 1584312)

CONTINGENCY CELL PHONE PLAN ON-TASK BEHAVIOR 28

Lenhart, A. (2010). Teens and mobile phones. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from

http://www.pewinternet.org/2010/04/20/teens-and-mobile-phones/

Moore, D. W., Anderson, A., Glassenbury, M., Lang, R., & Didden, R. (2013). Increasing on-

task behavior in students in a regular classroom: Effectiveness of a self-management

procedure using a tactile prompt. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22, 302-311.

doi:10.1007/s10864-013-9180-6

Panahon, C., & Martens, B. (2013). A comparison of non-contingent plus contingent

reinforcement to contingent reinforcement alone on students' academic performance.

Journal of Behavioral Education, 22, 37-49. doi:10.1007/s10864-012-9157-x

Skinner, C. H. (2002). An empirical analysis of interspersal research: Evidence, implications,

and applications of the discrete task completion hypothesis. Journal of School

Psychology, 40, 347-368. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00101-2

United States Census Bureau. (2014). Gilroy, california quick facts [Data file]. Retrieved from

http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/0629504

Vandenberg, N. (2001). The use of a weighted vest to increase on-task behavior in children with

attention difficulties. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55, 621–628.

doi:10.5014/ajot.55.6.621

Wei, F., & Wang, Y. (2010). Students' silent messages: Can teacher verbal and nonverbal

immediacy moderate student use of text messaging in class?. Communication Education,

59, 475-496. doi:10.1080/03634523.2010.496092

Wills, H., & Mason, B. (2014). Implementation of a self-monitoring application to improve on-

task behavior: A high-school pilot study. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23, 421-434.

doi:10.1007/s10864-014-9204-x